Along with falling from cultural Hindu nationalism to empty secular-territorial nationalism, the BJP has also fallen from solidarity with other oppressed and colonised nations to a short-sighted ethnocentrism. – Dr. Koenraad Elst

The BJP’s subordination of any and every ideological or religious conflict to questions of “national unity and integrity”, this most mindless form of territorial nationalism, is also a worrying retreat from the historical Hindu conception of Indian nationhood and its implications for the evaluation of foreign problems of national unity. Along with Mahatma Gandhi and other Freedom Fighters, the BJS used to be convinced that India was a self-conscious civilisational unit since several thousands of years, strengthened in its realisation of unity by the Sanskrit language, the Brahmin caste, the pilgrimage cycles which brought pilgrims from every part of India all around the country (“country” rather than the “Subcontinent” or “South Asia”, terms which intrinsically question this unity), and other socio-cultural factors of national integration. The notions that India was an artificial creation of the British and a “nation in the making”, were floated by the British themselves and by Jawaharlal Nehru, respectively, and both are obvious cases of unfounded self-flattery. Gandhi’s and the BJS’s viewpoint that India is an ancient nation conscious of its own unity is historically more accurate.

In foreign policy, one can expect two opposite attitudes to follow from these two conceptions of India, the Gandhian one which derives India’s political unity from a pre-existent cultural unity, and the Nehruvian one which denies this cultural unity and sees political unity as a baseless coincidence, an artificial creation of external historical forces. In its own self-interest, an artificially created state devoid of underlying legitimacy tends to support any and every other state, regardless of whether that state is the political embodiment of a popular will or a cultural coherence. The reason is that any successful separatism at the expense of a fellow artificial state is a threat to the state’s own legitimacy. That is, for instance, why the founding member states of the Organisation of African Unity decided from the outset that the ethnically absurd colonial borders were not to be altered. It is also why countries like Great Britain and France, whose own legitimacy within their present borders is questioned by their Irish, Corsican and other minorities, were reluctant to give diplomatic recognition to Lithuania when it broke away from the Soviet Union.

By contrast, those who believe that states are merely political instruments in the service of existing ethnic or cultural units, accept that state structures and borders are not sacrosanct in themselves and that they may consequently be altered. That is why Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn proposed to allow the non-Slavic republics to leave the Soviet Union, and why as a sterling Russian patriot he pleaded in favour of Chechen independence from the Russian Federation: it is no use trying to keep Turks and Slavs, or Chechens and Russians, under one roof against their will. If Russia is meant to be the political expression of the collective will of the Russian people, it is only harmful to include other nations by force, as the Chechens and Turkic peoples once were.

To be sure, even partisans of this concept of “meaningful” (as opposed to arbitrary) states will concede that there may be limitations to this project of adjusting state structures and state borders to existing ethnic and cultural realities, especially where coherent communities have been ripped apart and relocated, as has happened in Russia. Also, cultural and ethnic identities are not static givens (e.g. the “Muslim” character of India’s principal minority), so we should not oversimplify the question to an idyllic picture of a permanent division of the world in states allotted to God-given national entities. But at least the general principle can be accepted: states should as much as possible be the embodiment of coherent cultural units. That, at any rate, is the Hindu-nationalist understanding of the Indian state: as the political embodiment of Hindu civilisation.

Now, what is the position of the BJS/BJP regarding the right of a state to self-preservation as against the aspirations of ethnic-cultural communities or nations? The BJS originally had no problem supporting separatism in certain specific cases, esp. the liberation of East Turkestan (Sinkiang/Xinjiang), Inner Mongolia and Tibet from Chinese rule. At the time, the BJS still adhered to the Gandhian position: India should be one independent state because it is one culturally, and so should Tibet for the same reason. Meanwhile, however, this plank in its platform has been quietly withdrawn.

As A.B. Vajpayee told the Chinese when he was Janata Party Foreign Minister, and as Brijesh Mishra, head of the BJP’s Foreign Policy Cell, reconfirmed to me (February 1996): India, including the BJP, considers Tibet and other ethnic territories in the People’s Republic as inalienable parts of China.[1] The BJP has decisively shifted towards the Nehruvian position: every state, by virtue of its very existence, must be defended against separatist tendencies, no matter how well-founded the latter may be in cultural, ethnic or historical respects. That is, for example, why the BJP is not supporting Kurdish sovereignty against Iraqi and Turkish imperialism.[2] Along with falling from cultural Hindu nationalism to empty secular-territorial nationalism, the BJP has also fallen from solidarity with other oppressed and colonised nations to a short-sighted ethnocentrism.

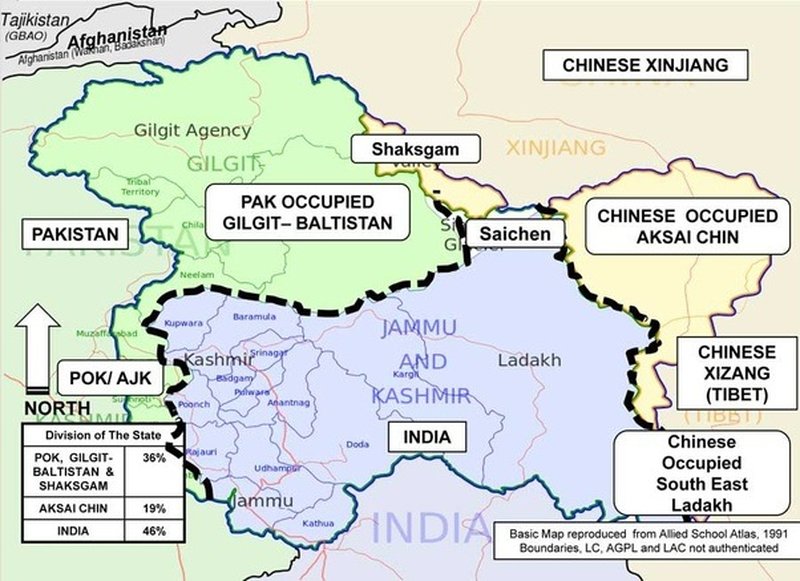

When you ask why the BJP has abandoned its support for the Tibetan freedom movement, the standard reply is that this would justify other separatisms, including those in Kashmir and Punjab. Exactly the same position is taken by non-BJP politicians and diplomats. But from a Hindu and from an Indian nationalist viewpoint, this position does injustice to India’s claim on Kashmir and Punjab, which should not be put on a par with all other anti-separatism positions in the world. Firstly, while Tibet was never a part of China, and while Chechnya was only recently (19th century) forcibly annexed to Russia, Kashmir and Punjab have been part of the heartland of Hindu culture since at least 5,000 years. Secondly, in contrast with the annexations of Chechnya and Tibet, the accession of Punjab (including the nominally independent princedoms in it) and the whole of the former princedom of Jammu & Kashmir to the Republic of India were entirely legal, following procedures duly agreed upon by the parties concerned.

Therefore, Indian nationalists are harming their own case by equating Kashmiri separatism with independentism in Tibet, which did not accede to China of its own free will and following due procedure, and which was not historically a part of China. To equate Kashmir with Tibet or Chechnya is to deny the profound historical and cultural Indianness of Kashmir, and to undermine India’s case against Kashmiri separatism. Here again, we see the harmful effect of the BJP’s intellectual sloppiness.

To be fair, we should mention that the party considers its own compromising position on Tibet as very clever and statesmanlike: now that it is preparing itself for Government, it is now already removing any obstacles in the way of its acceptance by China and the USA (who would both be irritated with the “destabilising” impact of a Government in Delhi which is serious about challenging Beijing’s annexation of Tibet). In reality, a clever statesman would reason the other way around: possibly there is no realistic scope for support to Tibetan independence, but then that can be conceded at the negotiation table, in exchange for real Chinese concessions, quid pro quo.[3] If you swallow your own hard positions beforehand, you will have nothing left to bargain with when you want to extract concessions on the other party’s hard positions, i.e., China’s territorial claims on Ladakh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, and its support to Burmese claims on the Andaman and Nicobar islands. International diplomacy should teach the BJP what it refuses to learn from its Indian experiences, viz. that being eager to please your enemies doesn’t pay. – Pragyata, 13 May 2020 (excerpt taken from BJP vis-a-vis Hindu Resurgence by Koenraad Elst and published by Aditya Prakashan, New Delhi).

› Belgian scholar Dr Koenraad Elst is an author, linguist, and historian who visits India often to study and lecture.

References

- If earlier BJP manifestos still mentioned Sino-Indian cooperation “with due safeguards for Tibet”, meaningless enough, the 1996 manifesto does not even mention Tibet. Nor does it unambiguously reclaim the China-occupied Indian territories; it vaguely settles for “resolv[ing] the border question in a fair and equitable manner”.(p.32)

- In October 1996, a handful of BJP men bravely demonstrated before the American Embassy against the American retaliation to the Iraqi troops’ entry in the Kurdish zone from which it was barred by the UNO. There was every reason to demonstrate: while punishing Iraq, the Americans allow Turkish aggression against Iraqi Kurdistan, the so-called “protected” zone, and fail to support Kurdish independence in deference to Turkey’s objections. But that was not the target of the BJP protest, which merely opposed any and every threat against the “unity and integrity” of Iraq, a totally artificial state with artificial and unjustifiable borders (as Saddam Hussain himself argued during the Gulf War, pointing to the artificial British-imposed border between the Mesopotamian population centre and the Kuwaiti oil fields).

- This is not to suggest that demanding freedom for Tibet should only be done to have a bargaining chip, merely to illustrate the principle that concessions, even if unavoidable under the circumstances, should still be made known as such, i.e. in exchange for concessions from the other party, and not made beforehand in exchange for nothing. But Beijing politics may develop in such a way that Tibetan sovereignty becomes a realistic proposition again.