The cult of Christianity has an incalculable amount of blood on its hands. And the Jesus tale seems to have been nothing more than oral legend, with plenty of hoax and fraud perpetrated along the ages. – Michael Paulkovich

Most historians hold the position I had once harbored as true, being a Bible skeptic but not a Christ mythicist. I had maintained that the Jesus person probably existed, having fantastic and impossible stories later foisted upon his earthly life, passed by oral tradition then recorded many decades after Jesus lived.

After exhaustive research for my first book, I began to perceive both the brilliance and darkness from history. I discovered that many early Christian fathers believed with all pious sincerity their savior never came to earth—or when he did, it was Star-Trekian style, beamed down pre-haloed and fully-grown, sans transvaginal egress. Moreover I expose many other startling bombshells in my book No Meek Messiah: Christianity’s Lies, Laws, and Legacy.

I embarked upon one exercise to revive research into Jesus-era writers who should have recorded Christ tales, but did not. John Remsburg enumerated forty-one “silent” historians in his book The Christ (1909). I dedicated months of research to augment Remsburg’s list, finally tripling his count. In No Meek Messiah I provide a list of 126 writers who should have recorded something of Jesus, with exhaustive references.

Perhaps the most bewildering “silent one” is the mythical super-savior himself, Jesus the Son of God ostensibly sent on a suicide mission to save us from the childish notion of “Adam’s Transgression” as we learn from Romans 5:14. The Jesus character is a phantom of a wisp of a personage who never wrote anything. So, add one more: 127.

The Jesus character is a phantom

Jesus is lauded as a wise teacher, savior, and a perfect being. Yet Jesus believed in Noah’s Ark (Mt. 24:37, and Lk. 17:27), Adam and Eve and their son Abel (Lk. 3:38 and Lk. 11:51), Jonah living in a fish or whale (Mt. 12:40), and Lot’s wife turning into salt (Lk. 17:31-32). Jesus believed “devils” caused illness, and even bought into the OT notion (Jn. 3:14) that a magical pole proffered by the OT (Num. 21:9) could cure snake bites merely by gazing upon it.

Was Jesus smarter than a fifth grader?

But perhaps no man is more fascinating than Apollonius Tyaneus, saintly first century adventurer and noble paladin. Apollonius was a magic-man of divine birth who cured the sick and blind, cleansed entire cities of plague, foretold the future and fed the masses. He was worshipped as a god, and son of god. Despite such nonsense claims, Apollonius was a real man recorded by reliable sources.

As Jesus ostensibly performed miracles of global expanse (e.g. Mt. 27), his words going “unto the ends of the whole world” (Rom. 10), one would expect virtually every literate person on earth to record those events during his time. A Jesus contemporary such as Apollonius should have done so, as well as those who wrote of Apollonius. Such is not the case. In Philostratus’ third century chronicle, Vita Apollonii, there is no hint of Jesus. Nor in the works of other Apollonius epistolarians and scriveners: Emperor Titus, Cassius Dio, Maximus, Moeragenes, Lucian, Soterichus Oasites, Euphrates, Marcus Aurelius, or Damis of Hierapolis. It seems none of these writers from first to third century ever heard of Jesus, global miracles and alleged worldwide fame be damned.

Another bewildering author is Philo of Alexandria. He spent his first century life in the Levant, even traversing Jesus-land. Philo chronicled Jesus contemporaries—Bassus, Pilate, Tiberius, Sejanus, Caligula—yet knew nothing of the storied prophet and rabble-rouser enveloped in glory and astral marvels. Historian Josephus published Jewish War ca. 95. He had lived in Japhia, one mile from Nazareth—yet Josephus seems to have been unaware of both Nazareth and Jesus. (I devoted a chapter to his interpolated works, pp. 191-198.) You may encounter Christian apologists claiming that Pliny the Younger, Tacitus, Suetonius, Phlegon, Thallus, Mara bar-Serapion, or Lucian wrote of Jesus contemporary to the time. In No Meek Messiah I thoroughly debunk such notions.

The Bible venerates the artist formerly known as Saul of Tarsus, an “apostle” essentially oblivious to his heavenly saviour. Paul is unaware of the virgin mother, and ignorant of Jesus’ nativity, parentage, life events, ministry, miracles, apostles, betrayal, trial and harrowing passion. Paul knows neither where nor when Jesus lived, and considers the crucifixion metaphorical (Gal. 2:19-20). Unlike the absurd Gospels, Paul never indicates Jesus had been to earth. And the “five hundred witnesses” claim (1 Cor. 15) is a well-known forgery.

Qumran, the stony and chalky hiding place for the Dead Sea Scrolls lies twelve miles from Bethlehem. The scroll writers, coeval and abutting the holiest of hamlets one jaunty jog eastward never heard of Jesus. Dr. Jodi Magness wrote, “Contrary to claims made by a few scholars, no copies of the New Testament (or precursors to it) are represented among the Dead Sea Scrolls.“

Christianity was still wet behind its primitive and mythical ears in the second century, and Christian father Marcion of Pontus in 144 CE denied any virgin birth or childhood for Christ—Jesus’ infant circumcision (Lk. 2:21) was thus a lie, as well as the crucifixion! Marcion claimed Luke was corrupted, and his saviour self-spawned in omnipresence, a spirit without a body (see Dungan, 43). Reading the works of second century Christian father Athenagoras, one never encounters the word Jesus (or Ἰησοῦς or Ἰησοῦν, as he would have written)—Athenagoras was thus unacquainted with the name of his saviour it would seem. Athenagoras was another pious early Christian, unaware of Jesus (see also Barnard, 56).

The original booklet given the name “Mark” ended at 16:8, later forgers adding the fanciful resurrection tale (see Ehrman, 48). The booklet “John” in chapter 21 also describes post-death Jesus tales, another well-known and well-documented forgery (see Encyclopedia Biblica, vol. 2, 2543). Millions should have heard of the Jesus “crucifixion” with its astral enchantments: zombie armies and meteorological marvels (Mt. 27) recorded not by any historian, but only in the dubitable scriptures scribbled decades later by superstitious yokels. The Jesus saga is further deflated by the reality of Nazareth, having no settlement until after the 70 CE war—suspiciously around the time the Gospels were concocted, as René Salm demonstrates in his book. I also include in my book similarities of Jesus to earlier God-sons, too striking to disregard. The Oxford Classical Dictionary and Catholic Encyclopedia, as well as many others, corroborate. Quite a few son-of-gods myths existed before the Jesus tales, with startling similarities, usually of virgin mothers, magical births and resurrection: Sandan, Mithra, Horus, Attis, Buddha, Dionysus, Krishna, Hercules, Isiris, Orpheus, Adonis, Prometheus, etc.

The one true religion

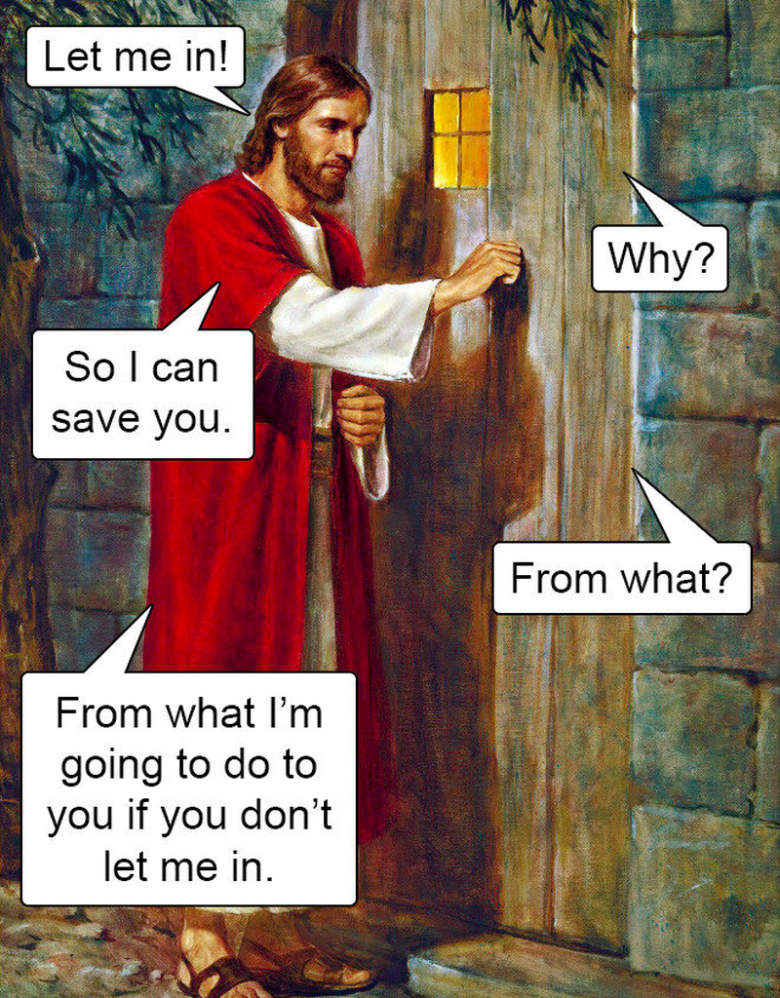

If you encounter a Christian defending her faith purely based on its popularity, you would do well to inform her that Christianity was a very minor cult in the fourth century, while “pagan” religions, especially Mithraism, were much more popular in the Empire—and the Jesus cult would have faded into oblivion if not for an imperial decree.

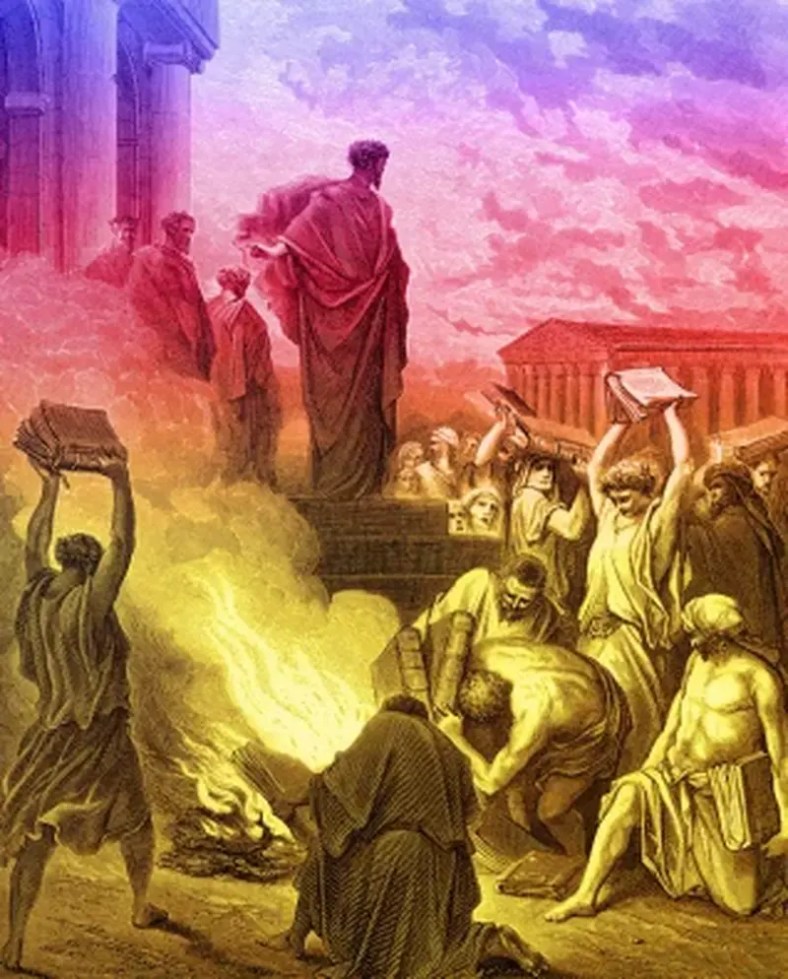

From No Meek Messiah: It is 391 CE now as Roman Emperor Theodosius elevates Jesus (posthumously) to divinity, declaring Christianity the only “legitimate” religion of the world, under penalty of death. The ancient myth is rendered law. This decision by Theodosius is possibly the worst ever made in human history: what followed were century after century of torture and murder in the name of this false, faked, folkloric “prophesied saviour” of fictional virgin mother. Within a year after the decree by Theodosius, crazed Christian monks of Nitria destroy the majestic Alexandrian Library largely because philosophy and science are taught there—not the Bible. In Alexandria these are times of the highest of intellectual pursuits, all quashed by superstitious and ignorant Christians of the most godly and murderous variety: they had the “Holy Bible” on their side.

Emperor Theodosius I could have had no idea how much harm this blunder would cause humanity over the centuries that followed. Christianity was made the only legal cult of the empire, and for the next 1500 years, good Christians would murder all non-Christians they could find by the tens of millions.

Frauds and forgeries

Along the centuries the Church has sought to gain power and wealth, and No Meek Messiah exposes their many scams and deceits and obfuscations in detail including:

- Abgar Forgeries (4th century)

- Apostolic Canons (400 CE)

- Hypatia the Witch (415 CE)

- Symmachian Forgeries (6th century)

- St. Peter Forgery (ca. 751)

- False “Donation of Constantine” (8th century)

- False Decretals (8th century)

- Extermination of the Cathar “witches” (13th century)

- Murder of the Stedinger “devils” (1233)

- The Manifest Destiny decree (1845) and eradication of Native Americans

- Invention of the “Immaculate Conception” (1854)

- The Lateran Treaty (1929)

The good that Jesus brought

Early Christians believed all necessary knowledge was in the Bible and thus closed down schools, burned books, forbade teaching philosophy and destroyed libraries. The Jesus person portrayed in the Bible taught that “devils” and “sin” cause illness, and thus for some 1700 years good Christians ignored science and medicine to perform exorcisms on the ill.

The Bible decrees “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live” (Ex. 22:18, with support from Dt. 18:10-12, Lev. 20:27, 2 Chr. 33:6, Micah. 5:12, and 1 Sam. 28:3). In the New Testament, Paul in Galatians 5:19-21 joins the anti-witchcraft credo. But let’s face it: Paul claims to be a devoted Hebrew, full of credulity and misogyny. Paul will “suffer not a woman to teach” and thus along the centuries women have been second-class citizens, especially within the Church. These juvenile and immoral Bible edicts are not left in the past.

From No Meek Messiah: Remember the witch hunts? Long ago and far away, past atrocities forgotten? So perhaps we should forgive and forget. Around the world, the Christian Bible is still used to accuse people, usually children, of “witchcraft” and to punish them. Refer to The Guardian, Sunday, 9 December 2007, “Child ‘witches’ in Africa”; Huffington Post, October 18, 2009, “African Children Denounced As ‘Witches’ By Christian Pastors”; and The Guardian, Friday 31 December 2010, “Why are ‘witches’ still being burned alive in Ghana?” The scripture normally cited regarding witches is Exodus 22:18, and there are many more. In Ghana, a study found that “accused witches were physically brutalised, tortured, neglected, and in two cases, murdered.” In Kinshasa, Congo, “80% of the 20,000 street children … are said to have been accused of being witches.” Even to this day the Bible’s proclamations against witches are still considered valid by many Christians. In places like Indonesia, Tanzania, the Congo and Ghana superstitious fundamental Christians actively pursue and execute witches, including murdering child “sorcerers.” In Malawi, accused witches are routinely jailed.

Christians are typically kept ignorant of certain evil and immoral words placed into the mouth of this mythical mystery-man:

“If any man come to me, and HATE NOT his father, and mother, and wife, and children, and brethren, and sisters, yea, and his own life also, he cannot be my disciple.” – Luke 14:26.

Jesus is actually portrayed as a pitiful man in desperate need of praise:

“He that loveth father or mother more than me is not worthy of me: and he that loveth son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me.” – Matt. 10:37.

Not only does Jesus never advise against slavery, but he recommends savage whipping of disobedient slaves:

“And that servant, which knew his lord’s will, and prepared not himself, neither did according to his will, shall be beaten with many stripes.” – Luke 12:47.

Jesus has nothing against stealing, as he instructs his apostles to pinch a horse and a donkey from their rightful owner:

“And when they drew nigh unto Jerusalem, and were come to Bethphage, unto the Mount of Olives, then sent Jesus two disciples, Saying unto them, Go into the village over against you, and straightway ye shall find an ass tied, and a colt with her: loose them, and bring them unto me. And if any man say ought unto you, ye shall say, The Lord hath need of them; and straightway he will send them.” – Matt. 21:1-3.

Gentle and meek and mythical

I personally know several Christians who accept evolution as scientific fact. Okay, they kind of ignore the Old Testament, but I asked one born again Christian about the genealogy of Jesus and she was only aware of another one in Luke.

From No Meek Messiah: Christianity absolutely depends on mythical “Adam.” Without Adam, Eve, and a talking snake, Jesus’ mission is moot and pointless and void. Christians are generally oblivious of this because they have been shown a genealogy in Matthew (which only goes back to “Abraham”), and are rarely if ever exposed to Luke’s disparate and childlike version—which if true would negate all of evolution and in fact most known history and science. According to the anonymous author of Luke, a mere seventy-five generations separate “Adam”—and the beginning of the universe—from the birth of Jesus some 2,000 years ago.

This “meek” messiah boasted he was “greater than Solomon” (Mt. 12:42), saying he “came not to send peace, but a sword” (Mt. 10:34), and (Lk. 12:49). Jesus desperately needs your praise (Mt. 10:37), and advises you to beat your slaves.

This Jesus character speaks highly of father Yahweh‘s genocidal tantrums in Matthew 11:20-24. Jesus is referring to the book of Joshua where his father declares he will wipe out all people of Sidon: “All the inhabitants of the hill country from Lebanon unto Misrephoth-maim, and all the Sidonians, them will I drive out from before the children of Israel”.

You may have heard Christians claim that the only “god hates fags” verbiage comes from the Old Testament (Lev. 18:22), but both Paul (in Rom. 1:26-27) and Jesus speak out against it, as the J-man praises the ruin of Gaytown, Canaan: “But the same day that Lot went out of Sodom it rained fire and brimstone from heaven and destroyed them all.” – Luke 17:29.

Onward Christian soldiers

Christianity has a violent “holy book” as its authority, granting followers supremacy over the entire earth (e.g. Gen. 1:28) which they used to justify land grabs, genocide and holy conflicts. The following wars were perpetrated by Christians in the name of their saviour:

- War against the Donatists, 317 CE

- Roman-Persian War of 441 CE

- Roman-Persian War of 572-591 CE

- Charlemagne’s War against the Saxons, 8th century

- Spanish Christian-Muslim War of 912-928

- Spanish Christian-Muslim War of 977-997

- Spanish Christian-Muslim War of 1001-1031

- First Crusade, 1096

- Jerusalem Massacre, 1099

- Second Crusade, 1145-1149

- Spanish Christian-Muslim War, 1172-1212

- Third Crusade, 1189 CE

- War against the Livonians, 1198-1212

- Wars against the Curonians and Semigallians, 1201-90

- Fourth Crusade, 1202-04

- Wars against Saaremaa, 1206-61

- War against the Estonians, 1208-1224

- War against the Latgallians and Selonians, 1208-1224

- Children’s Crusade, 1212

- Fifth Crusade, 1213

- Sixth Crusade, 1228 War against the Livonians, 1198-1212

- Spanish Christian-Muslim War, 1230-1248

- Seventh Crusade, 1248

- Eighth Crusade, 1270

- Ninth Crusade, 1271-1272

- The Inquisitions

- War against the Cathars, 1209-1229 and onward

- War against the Stedingers of Friesland, 1233

- Spanish Christian-Muslim War, 1481-1492

- Four Years War of 1521-26

- Count’s War of 1534-36

- Schmalkaldic War, 1546

- Anglo-Scottish War of 1559-1560

- First War of Religion,1562

- Second War of Religion, 1567-68

- Third War of Religion, 1568-70

- Fourth War of Religion, 1572-73

- Fifth War of Religion, 1574-76

- Sixth War of Religion, 1576-77

- Seventh War of Religion, 1579-80

- Eighth War of Religion, 1585-98

- War of the Three Henrys, 1588

- Ninth War of Religion, 1589—1598

- Ottoman-Habsburg wars, 15th to 16th century

- War against the German Farmers (“peasants”), 16th Century

- The French Wars of Religion, 16th Century

- Shimabara Revolt, 1637

- Covenanters’ Rebellion of 1666

- Covenanters’ Rebellion of 1679

- Covenanters’ Rebellion of 1685

- The Thirty Years War, 17th Century

- The Irish rebellion of 1641

- Spanish Christian extermination of South American natives

- Manifest Destiny

- War of the Sonderbund, 1847

- Crimean War, 1853-1856

- Tukulor-French War, 1854-1864

- Taiping Rebellion, 1851 and 1864

- Serbo-Turkish War, 1876-78

- Russo-Turkish War, 1877-1878

- Russian Revolution, killing of Jews, late 19th century

- First Sudanese Civil War, 1955-1972

- Nigerian Civil War, 1967

- Lebanese Civil War, 1975

- Sabra and Shatila massacre, 1982

- Second Sudanese Civil War, 1983

- Yelwa Massacre, 2004

- Bosnian War, 1992-1995

A relatively unknown contrivance occurred in the thirteenth century when Pope Innocent III ordered a genocidal attack against the entire region of Languedoc France. The pope depicted the Cathars as witches; of being cannibals; desecrating the cross; and having “sexual orgies.”

Yet malefic sounds of sibilance emanated only from the Vatican, and not from its contrived enemies living peaceably in France with their pure and righteous ways. The Church murdered over a million innocent Cathars over the period of 35 years—men, women, children. Christian forces wiped them from the face of the planet. At the height of the siege, Christian forces were burning hundreds at the stake at a time. The Christian colossus exterminated them, then annexed much of Languedoc—some for the Church, some from northern French nobles. The extravagant Palais de la Berbie (construction began in 1228) and the Catholic fortress-cathedral Sainte Cécile (began 1282) are just two examples that remain to this day.

Conclusion

When I consider those 126 writers, all of whom should have heard of Jesus but did not, and Paul and Marcion and Athenagoras and Matthew with a tetralogy of opposing Christs, the silence from Qumran and Nazareth and Bethlehem, conflicting Bible stories, and so many other mysteries and omissions, I must conclude this “Jesus Christ” is a mythical character. “Jesus of Nazareth” was nothing more than urban (or desert) legend, likely an agglomeration of several evangelic and deluded rabbis who might have existed.

The “Jesus mythicist” position is regarded by Christians as a fringe group. But after my research I tend to side with Remsburg—and Frank Zindler, John M. Allegro, Thomas Paine, Godfrey Higgins, Robert M. Price, Charles Bradlaugh, Gerald Massey, Joseph McCabe, Abner Kneeland, Alvin Boyd Kuhn, Harold Leidner, Peter Jensen, Salomon Reinach, Samuel Lublinski, Charles-François Dupuis, Rudolf Steck, Arthur Drews, Prosper Alfaric, Georges Ory, Tom Harpur, Michael Martin, John Mackinnon Robertson, Alvar Ellegård, David Fitzgerald, Richard Carrier, René Salm, Timothy Freke, Peter Gandy, Barbara Walker, Thomas Brodie, Earl Doherty, Bruno Bauer and others—heretics and iconoclasts and freethinking dunces all, according to “mainstream” Bible scholars.

If all this evidence and non-evidence including 126 silent writers cannot convince, I’ll wager we will uncover much more. Yet this is but a tiny tip of the mythical Jesus iceberg: nothing adds up for the fable of the Christ. In the Conclusion of No Meek Messiah I summarise the madcap cult of Jesus worship that has plagued the world for centuries. It should be clear to even the most devout and inculcated reader that it is all up for Christianity, and in fact has been so for centuries. Its roots and foundation and rituals are borrowed from ancient cults: there is nothing magical or “God-inspired” about them. The “virgin birth prophecy” as well as the immaculate conception claims are fakeries, the former due to an erroneous translation of the Tanakh, the latter a nineteenth century Catholic apologetic contrivance, a desperate retrofitting.

Jesus was no perfect man, no meek or wise messiah: in fact his philosophies were and are largely immoral, often violent, as well as shallow and irrational. There have been many proposed sons of god, and this Jesus person is no more valid or profound than his priestly precursors. In fact, his contemporary Apollonius was unquestionably the superior logician and philosopher.

Christianity was a very minor and inconsequential cult founded late in the first century and then—while still quite minor—forced upon all the people of the Empire, and all rival kingdoms in the fourth century and beyond, as enforceable law with papal sanction. Christianity has caused more terror and torture and murder than any similar phenomenon. With its tyrannical preachments and directives for sightless and mindless obedience, the Bible is a violent and utterly useless volume, full of lies and immoral edicts and invented histories, no matter which of the many “versions” you may choose to read—including Thomas Jefferson’s radical if gallant abridgement.

The time to stop teaching the tall tales and nonsense to children, frightening them with eternal torture administered by God’s minions, has long ago passed. Parents who do so are likely deluded, and most surely are guilty of child abuse of the worst sort….

The cult of Christianity has an incalculable amount of blood on its hands. And the “Jesus” tale seems to have been nothing more than oral legend, with plenty of hoax and fraud perpetrated along the ages. It is my hope that mankind will someday grow up and relegate the Jesus tales to the same stewing pile that contains Zeus and his son Hercules, roiling away in their justifiable status as mere myth. – JNE, 19 July 2014

Bibliography

- Catholic Encyclopedia, first edition. The Encyclopedia Press, 1907-1913.

- Dungan, David L., Constantine’s Bible, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2007.

- Ehrman, Bart, Jesus, Interrupted, New York: HarperCollins, 2009.

- Encyclopedia Biblica: A Critical Dictionary of the Literary, Political and Religious History: The Archeology, Geography and Natural History of the Bible, Edited by Thomas Kelly Cheyne and J. Sutherland Black. 1899.

- Magness, Jodi, The Archaeology of Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002.

- Oxford Classical Dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Salm, René, The Myth of Nazareth, Parsippany: American Atheist Press, 2008.

Further Reading

- Alfaric, Prosper, Jésus a-t-il existé? 1932.

- Allegro, John M., The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Christian Myth, Amherst: Prometheus Books, 1992.

- Barnard, Leslie William, Athenagoras: A Study in Second Century Christian Apologetic, Paris: Éditions Beauchesne, 1972.

- Bradlaugh, Charles, Who Was Jesus Christ? London: Watts and Co., 1913.

Brodie, Thomas, Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery, Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix, 2012. - Carrier, Richard, Proving History: Bayes’s Theorem and the Quest for the Historical Jesus, Amherst: Prometheus, 2012.

- Doherty, Earl, Neither God nor Man, Ottawa: Age of Reason, 2009.

- Drews, Arthur, Hat Jesus gelebt? Mainz: 1924.

- Dupuis, Charles-François, L’origine de tous les cultes, ou la religion universelle, Paris: 1795.

- Ellegård, Alvar, Jesus One Hundred Years Before Christ, New York: Overlook Press, 2002.

- Fitzgerald, David, Nailed: Ten Christian Myths That Show Jesus Never Existed at All, Lulu.com, 2010.

- Freke, Timothy, and Gandy, Peter, The Jesus Mysteries: Was the “Original Jesus” a Pagan God? New York: Three Rivers Press, 1999.

- Harpur, Tom, The Pagan Christ: Recovering the Lost Light, Toronto: Thomas Allen Publishers, 2005.

- Higgins, Godfrey, Anacalypsis, A&B Books, 1992.

- Jensen, Peter, Moses, Jesus, Paul: Three Variations on the Babylonian Godman Gilgamesh, 1909.

- Kneeland, Abner, A Review of the Evidences of Christianity, Boston: Free Enquirer, 1829.

- Kuhn, A. B., Who Is This King of Glory? Kessinger Publishing, LLC; Facsimile Ed edition, 1992.

- Leidner, Harold, The Fabrication of the Christ Myth, Survey Press, 2000.

- Lublinski, Samuel, Die Entstehung des Christentums; Das werdende Dogma vom Leben Jesu, Köln: Eugen Diederichs, 1910.

- Martin, Michael, Atheism: A Philosophical Justification, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992.

- Massey, Gerald, Ancient Egypt, the Light of the World, Sioux Falls: NuVision, 2009.

- McCabe, Joseph, The Myth of the Resurrection and Other Essays, Amherst: Prometheus Books, 1993.

- Ory, Georges, Le Christ et Jésus, Paris: Éditions du Pavillon, 1968.

- Paine, Thomas, The Age of Reason, Paris: Barrots, 1794.

- Price, Robert M., Deconstructing Jesus, Amherst: Prometheus, 2000.

- Price, Robert M., The Case Against the Case for Christ, Cranford: American Atheist Press, 2010.

- Reinach, Salomon, Orpheus, a History of Religions, New York: Liveright, 1933.

- Remsburg, John, The Christ, New York: Truth Seeker, 1909. Reprinted by Prometheus Books, 1994.

- Robertson, John M., A Short History of Christianity, London: Watts & Co., 1902.

- Steck, Rudolf, Der Galaterbrief nach seiner Echtheit untersucht nebst kritischen Bemerkungen zu den Paulinischen Hauptbriefen, Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1888.

- Walker, Barbara, The Women’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets, New York: HarperOne, 1983.

- Zindler, Frank, The Jesus the Jews Never Knew, Cranford: American Atheist Press, 2003.

» Michael Paulkovich is an aerospace engineer, historical researcher, freelance writer, and a frequent contributor to Free Inquiry and Humanist Perspectives magazines. His book No Meek Messiah was published in 2013 by Spillix.