Archaeologist Dr. K.K. Muhammed, 71, was part of the Archaeological Survey of India team that excavated the Babri Masjid site in Ayodhya in 1976 where the Ram Temple now stands. While stating the demolition of Babri Masjid did shock him as an archaeologist, Dr. Muhammed is of the view Muslims must willingly hand over Gyanvapi and Mathura mosques to Hindus. He thinks that will heal many wounds. While stressing the Congress Party should have decided to participate in the inauguration of the Ram Temple on January 22, Dr. Muhammed terms the BJP rule under Narendra Modi a dark age for the ASI. Excerpts from his conversation with the New Indian Express Interrogation Team

Q : You were part of the ASI team that excavated Babri Masjid/Ram Janmabhoomi in 1976. What were your findings?

A : It was a team led by Professor B.B. Lal that carried out the excavation and I was part of it. We came across pillars of a Hindu temple, with poornakalasa engraved on them. Forms of defaced gods and goddesses were also discovered. Terracotta statues traditionally associated with temples, too, were unearthed. We will never find statues of humans in mosques, as these are haram for Muslims. That’s how we concluded that a temple had stood there before the mosque was constructed.

Q : But some, like Professor Syed Ali Rizvi of AMU, allege you were not part of the excavation team?

A : I was a postgraduate diploma student then at ASI’s School of Archaeology. Ten of us went as a team, including senior Congress leader Jairam Ramesh’s wife Jaisree Ramanathan. I was engaged in the excavation of Trench B.

Q : Have the findings of these studies been published in any academic journal?

Q : ASI excavations found structures to prove that there was a temple. … But was there any proof of it being a Ram Temple?

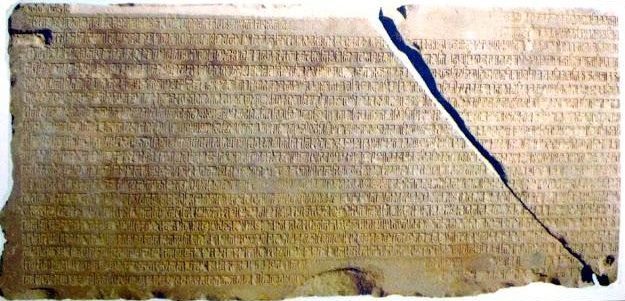

A : Yes. They got an inscription—Vishnuharisila Phalakam—after the masjid was demolished in 1992. It clearly states that this temple is dedicated to the Mahavishnu who killed Bali.

Q : So the crucial evidence was discovered during demolition, not during excavation?

A : Yes. They got this evidence after the Masjid demolition, not during excavation. The critics first said it was an 18th-century inscription. Later they backed out. In reality, it’s a 12th-century inscription. There was also an allegation that such evidence was planted there. So, we checked with the Lucknow Museum. They confirmed that the inscription they possess remains with them.

Q : The popular narrative is that Babar demolished a temple and constructed a masjid. But do we have evidence to prove that Babar had demolished the temple?

A : Babar’s military commander Mir Baqi (Baqi Tashqandi) had led the demolition of the temple. There was an inscription in Persian which said Mir Baqi had demolished the temple. It could also have been a dilapidated structure.

Q : But there is a huge difference between demolishing a temple to build a masjid and constructing a masjid on the ruins of a dilapidated temple….

A : Many temples were demolished in medieval India. If you visit Delhi you can see Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque near Qutub Minar (the mosque was built over the site of a temple). Some pages of Babar Nama have gone missing. Pages describing the activities of three months are missing. But there was an inscription that Mir Baqi had constructed the masjid. The demolition was part of a war and the Muslims of the current generation are in no way responsible for the act. But at the same time, Muslims should not defend the demolition of temples by some invaders. Christians do not justify what the Portuguese did in Goa.

Q : What were the findings of the 2003 excavations?

A : In 2003, a team led by B.R. Mani carried out an excavation using the Ground Penetrating Radar and found out there was a structure underneath. During the excavation, 12 pillars and more than 50 brick bases were discovered. The excavation team had experts from JNU/AMU in addition to the Waqf committee’s lawyers, VHP people and members of the judiciary. It was fully recorded. About one-fourth of the workers were Muslims.

Q : Going by what you say, there was a 12th-century temple, and later a masjid was built on top of it in the 16th century. As an archaeologist do you agree with the demolition of a structure to unearth another one?

A : No archaeologist would agree to the demolition of any historical structure. In this case, it had already been demolished. We now need to think about what’s the way forward.

Q : As an archaeologist, what did you feel when Babri Masjid was demolished in 1992?

A : We were all shaken. Senior IAS officer I. Mahadevan had stated that we should not do wrong to correct a historical mistake that happened centuries ago. We were all against the demolition. It shouldn’t have happened.

Q : And as an Indian Muslim?

A : An archaeologist can never be a Muslim or a Hindu. We look at such matters objectively. I have faced stiff opposition from the Muslim community and Hindu groups on various occasions.

Q : Similar demands are now being made about Gyanvapi and Mathura?

A : The Muslim community should be ready to willingly hand over its rights (to the structures at) Varanasi and Mathura, too, to the Hindus. Tension is bound to be there. But from a historic perspective, there cannot be a lasting solution to the whole issue without handing these two over. I always remind the Muslims that India, even after Partition, remains a secular country because of its Hindu majority.

Q : But won’t it lead to more tension?

A : Ayodhya, Kashi and Mathura are three places as important to Hindus as Mecca and Medina are to Muslims. Hence, Muslims should be ready to willingly hand over these places.

Q : Is there sufficient evidence in Gyanvapi to support claims of a temple there?

A : Yes. There may be Islamic inscriptions, but in totality, it is a Hindu structure. Also, there are many literatures which support this. This issue has created a major divide between the Hindus and the Muslims. So, handing it over to Hindus is the only lasting solution.

Q : Gyanvapi is an 18th century structure. As an archaeologist, do you support demolishing such an old structure?

A : The same issue had come up about Babri Masjid too. We can transplant these structures as such, without demolishing them. So far only four such transplants have been carried out in India. Of these, two were led by me—the Kurudi Mahadeva Temple and the Chaubis Avatar Temple in Madhya Pradesh.

Q : Whether Babri Masjid or Gyanvapi Mosque, these structures came into being as part of some historical moments. If we start correcting such historical errors, where would it lead us to?

A : That’s right. It’ll go on without any beginning or end. In Kerala itself, there are many such Buddhist temples and Jain temples that have later become Hindu temples. But if we take these three places as an exception—Ram Janmabhoomi, Krishna’s birthplace and Siva temple—that could prove to be the only and lasting solution to this issue. I think, if these two are handed over, all religious groups together can resolve this issue once and for all.

Q : Isn’t that just wishful thinking? The RSS-VHP reportedly has a list of close to 2,000 temples that were demolished to construct mosques….

A : There won’t be any end if we go on like this. But unlike Semitic religions, the Hindu mind will not approve of such aggressiveness. You have to remember that many Hindus have stood with the Muslims in the fight against the Ram Mandir movement. Can you remember one instance where the Muslims stood for the cause of the Hindus?

Q : Isn’t Ayodhya more of a political issue than an archaeological or historical issue?

A : Yes, correct. It’s a political issue. It’s a fact that the BJP and the RSS try to use it with a motive to make political gains. At the same time, we need to understand the pain of lakhs of ordinary Hindu devotees. It would have been better if the Muslims could understand the pain of the Hindus.

Q : But aren’t these emotions created by politicians?

A : I accept there were attempts to whip up emotions. But even during my visit to Ayodhya in 1976-77, I could understand the heart-wrenching agony of the poor Hindus. Had it been Mecca or Medina, how many bombs would have exploded by now? Hindus allowed that structure to remain there for 500 years. We have to understand this magnanimity of Indian culture and Hinduism.

Q : A 16th century structure has been demolished and a huge structure built using modern technology. Do you think justice has been served?

A : The issue is not whether the act is justified or not. The structure has been demolished. If it was not demolished, ASI would not have allowed the construction of another structure within 300 metres from the structure. The disputed structure has gone and the new building has been constructed considering the requirements of the current time. It is an issue of faith and we have to make some compromises.

Q : Do you think the Ram Temple issue had been a pan-India issue at any point of time?

A : It was not a pan-India issue. But now it is growing to such levels. I accept that it is a political project.

Q : You say the Hindus were magnanimous. Where can we see such large-hearted Hindus now?

A : Compared to (followers of) other religions, Hindus are far better even now. They may react recklessly, playing with emotions, but they will think and correct themselves later. The Semitic religions will never be ready to compromise on their faith.

Q : Do you think there is an attempt to Semiticise the Hindu religion?

A : Yes. The Semitic religions have started influencing Hinduism. But it is a temporary phenomenon and will not be sustained. I am more concerned about the false scientific claims of Pushpaka Vimana, surgery, and stem cells mooted by even educated people who are inspired by the Hindu revival. The king of Saudi Arabia will not present the claims of Arab mythology in a science congress. But PM Modi had presented the claims of Indian sages who pioneered surgery. This has created concerns that Hinduism is losing its values.

Q : The lock of Babri Masjid was opened, allowing pooja, during the term of former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. How significant was that move?

A : Opening the lock of the Masjid, in 1986, was the first important decision. Later, in 1989, he allowed pooja at the disputed structure. There was an unwritten agreement between renowned Islamic scholar Abdul Hassan Ali Nadwi and Rajiv Gandhi to solve the issue. The agreement was that if the Muslims allowed the opening of Babri Masjid, the government would bring a bill to overcome the Shah Bano case verdict.

Q : What happened then?

A : The Waqf committee, including Syed Shahabuddin, had favoured the agreement. But once the Shah Bano bill was passed, all except Abdul Hassan Ali Nadwi changed their stance. After Rajiv Gandhi’s death, the agreement was forgotten.

Q : It is rumoured that historian Irfan Habib played a role in scuttling the agreement. Is it true?

A : I don’t know about his role. I will not be objective while speaking about Irfan Habib, because I have personal enmity with him. He is my teacher but I have no respect for him.

Q : Do you think the stand of Kerala CPM in the Babri Masjid issue is inspired by arguments of the Marxist historians?

A : Irfan Habib plays a prominent role in influencing the stand of the Communists. Besides, the CPM took it as a political stand to win the support of Muslims. I found the stand of the Muslim League more acceptable.

Q : How do you see Congress’ decision not to attend the consecration ceremony?

A : Congress should have come forward in these things because Rajiv Gandhi took the initiative to open the lock of Babri Masjid. Congress should have understood the feelings of Hindus, but those who control Congress do not think along those lines.

Q : Do you mean to say the Congress failed to understand the north Indian Hindu psyche?

A : That’s what I feel. And they are also scared of the consequences. If Congress becomes irrelevant, who else is remaining? BJP has become a group that can stoop to any level. We feel sad in seeing the misuse of the agencies like the ED.

Q : But many consider you a BJP person?

A : That’s what people think. I didn’t attend their (BJP’s) meeting though they invited me. I can be considered a Congressman because I share their liberal ideology.

Q : Your book Njanenna Bharatheeyan has created a controversy because you stated that the ASI is in a dead state during the BJP rule?

A : Yes. The ASI has become a dead organisation and 10 years of BJP rule is a dark age of the organisation. I had undertaken the renovation of 80 temples that were destroyed in the earthquake in the Chambal area. We expected they (BJP) would be in the forefront of the renovation efforts. But not a single temple has been renovated in the last nine years.

Q : According to you, Modi has not shown any interest in renovating other temples, but was keen on Ayodhya temple. So, Modi’s interest in Ayodhya is not religious, but political?

A : They (BJP) themselves admit that it was a political project (laughs out). It is a mix of both (smiles).

Q : You are a person familiar with different archaeological structures. In your opinion, which are the most amazing structures in India?

A : Hampi and Halebidu in Karnataka. If they were renovated properly, they would be more beautiful than Rome.

Q : Have heard you saying that the collection of books that Hiuen Tsang took from India was the basis for China’s development?

A : (Hiuen Tsang) carried 751 books on the back of 20 horses to China. I-tsing carried with him 400 manuscripts. They translated these works and used them for their future growth. But our knowledge collections were destroyed by invaders.

Q : But isn’t it a usual practice for kings and emperors to destroy temples or mosques as part of the conquests? Do you think there is a religious undertone to it?

A : Damage is indeed a part of subjugation, but there is a religious undertone too in the case of Semitic religions. But in the case of Indian conquests of other countries, like Indonesia or Malaysia, you will not see this kind of destruction.

Q : But Marathas also ransacked many temples during their raids. … Similarly, Pandya king is said to have torched the Kanthaloor Sala in Thiruvananthapuram….

A : Yes … they ransacked temples, but they did not destroy them like Semitic invaders. Semitic religions think only they are correct.

Q : Is there any archaeological proof for the happenings in Ramayana and Mahabharata?

A : Yes. Events in Mahabharata must have happened after iron ore was discovered. As per our estimate, it happened between 1200 BC and 1300 BC. Ramayana happened in 1500 BC. There are archaeological findings in the regions between Kurukshetra and Mathura where events in Mahabharata may have unfolded.

Q : So, Ramayana and Mahabharata are not mythology but history?

A : Communists will say these are mythologies while right-wingers say it happened two lakh years before. Archaeologists will not accept any of these. Truth is actually in between. Mahabharata war must have been a tribal warfare, and not a world war as it has been made out (smiles).

Q : What are the changes that you have observed in Indian society since the day you joined ASI in 1976?

A : People in general have become more religious. This change is more evident in the case of Hindus. I would say Hindus are in a way being forced to be more organised like the Semitic religions.

Q : Upanishads are your favourite books?

A : Yes. I am a follower of Vivekananda (smiles).

Q : Heard you received many threats after the Ayodhya verdict?

A : Yes, there were threats. I had police security for three years. Even now I don’t go out frequently.

Q : Have you received an invitation for the consecration of the Ram Temple?

A : Yes. I have received an invitation. But I may not go due to health reasons. – The New Indian Express, 14 January 2024