One can conclude quite safely that Nehruvian Secularism is a magic formula for transmitting base metals into twenty-four carat gold. How else do we explain the fact of Islam becoming a religion, and that too a religion of tolerance, social equality, and human brotherhood; or the fact of Muslim rule in medieval India becoming an indigenous dispensation; or the fact of Sirajuddaula, Mir Qasim, Hyder Ali, Tipu Sultan, and Bahadur Shah Zafar becoming the heroes of India’s freedom struggle against British imperialism? – Sita Ram Goel

Nehruvian Secularism – Sita Ram Goel

Secularism per se is a doctrine which arose in the modem West as a revolt against the closed creed of Christianity. Its battle cry was that the State should be freed from the stranglehold of the Church, and the citizen should be left to his own individual choice in matters of belief. And it met with great success in every Western democracy.

Had India borrowed this doctrine from the modem West, it would have meant a rejection of the closed creeds of Islam and Christianity, and a promotion of the Sanatana Dharma family of faiths which have been naturally secularist in the modern Western sense. But what happened actually was that Secularism in India became the greatest protector of closed creeds which had come here in the company of foreign invaders, and kept tormenting the national society for several centuries.

We should not, therefore, confuse India’s Secularism with its namesake in the modern West. The Secularism which Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru propounded and which has prospered in post-independence India, is a new concoction and should be recognised as such. We need not bother about its various definitions as put forward by its pandits. We shall do better if we have a close look at its concrete achievements.

Going by those achievements, one can conclude quite safely that Nehruvian Secularism is a magic formula for transmitting base metals into twenty-four carat gold. How else do we explain the fact of Islam becoming a religion, and that too a religion of tolerance, social equality, and human brotherhood; or the fact of Muslim rule in medieval India becoming an indigenous dispensation; or the fact of Muhammad bin Qasim becoming a liberator of the toiling masses in Sindh; or the fact of Mahmud Ghaznavi becoming the defreezer of productive wealth hoarded in Hindu temples; or the fact of Muhammad Ghuri becoming the harbinger of an urban revolution; or the fact of Muinuddin Chishti becoming the great Indian saint; or the fact of Amir Khusru becoming the pioneer of communal amity; or the fact of Alauddin Khilji becoming the first socialist in the annals of this country; or the fact of Akbar becoming the father of Indian nationalism; or the fact of Aurangzeb becoming the benefactor of Hindu temples; or the fact of Sirajuddaula, Mir Qasim, Hyder Ali, Tipu Sultan, and Bahadur Shah Zafar becoming the heroes of India’s freedom struggle against British imperialism or the fact of the Faraizis, the Wahhabis, and the Moplahs becoming peasant revolutionaries and foremost freedom fighters?

One has only to go to the original sources in order to understand the true character of Islam and its above-mentioned luminaries. And one can see immediately that their true character has nothing to do with that with which they have been invested in our school and college text-books. No deeper probe is needed for unraveling the mysteries of Nehruvian Secularism.

This is not the occasion to go into the implications of this Secularism vis-a-vis India’s own spiritual vision, India’s own cultural wealth, India’s own national society, and India’s own native nationalism. I have dealt with this theme elsewhere. Suffice it to say that the other face of this Secularism is Hindu-baiting, which profession has been perfected by many scholars, scribes, and politicians, and has so far proved immensely profitable. I need not give the names. The stalwarts in this field are very well known.

What the hazrat and the shaheed Tipu Sultan stood for is described by Mir Hussain Ali Kirmani in his book, Nishan-i-Haidari, which he completed in AD 1802, three years after Tipu’s death. Kirmani writes:

“It happened one day that a fakir (a religious mendicant), a man of saint-like mind, passed that way, and seeing the Sultan gave him a life-bestowing benediction, saying to him, ‘Fortunate child, at a future time thou will be the king of this country, and when thy time comes, remember my words—take this temple and destroy it, and build a masjid in its place, and for ages it will remain a memorial of thee.’ The Sultan smiled, and in reply told him that ‘whenever, by his blessings, he should become a padishah, or king, he would do as he (the fakir) directed’. When, therefore, after a short time, his father became a prince, the possessor of wealth and territory, he remembered his promise, and after his return from Nagar and Gorial Bunder, he purchased the temple from the adorers of the image in it (which after all was nothing but the figure of a bull, made of brick and mortar) with their goodwill, and the Brahmins, therefore, taking away their image, placed it in the Deorhi Peenth, and the temple was pulled down, and the foundations of a new masjid raised on the site….”

That is the Masjid-i-Ala or Jama Masjid standing in Srirangapatanam on the site of a Hanuman temple. One need not comment on Kirmani’s statement that Tipu “purchased the temple from the adorers of the image … with their goodwill”. It is not unoften that terror has produced this sort of goodwill in the minds of its helpless victims. – Excerpted from the Preface to Tipu Sultan: Villain or Hero

Tipu Sultan: When an Islamist tyrant is turned into a freedom fighter and dharma saviour – Aabhas Maldahiyar

Karnataka is witnessing an Opposition backlash against a review committee set up by the state government that recommended doing away with the glorification of the alleged “rocket man” and freedom fighter, Tipu Sultan. The opposition led by the Congress, which was in power in the state between 2013 and 2018, has been parroting following three points to glorify Tipu Sultan:

- Tipu was the first freedom fighter of India;

- Tipu was the pioneer of war rockets;

- Tipu supported the temples and maths while Marathas looted them.

This essay intends to show how slippery and ill-founded these claims supporting Tipu Sultan are. Let’s begin.

“Who are my people? All of them—yes those that ring the temple bells and those that pray in the mosque—they are my people, and this land is theirs and mine.”

Above is a quote appearing from the work of fiction, The Sword of Tipu Sultan, written by novelist Bhagwan S. Gidwani in 1976. Unfortunately, this very work of fiction sets the narrative around how Indians should look at the “Tyrant of Mysore”.

Do you recall the following quote often attributed to Tipu Sultan, the Aurangzeb from south India?

“Every blow that is struck in the cause of American liberty throughout the world, in France, India and elsewhere and so long as a single insolent and savage tyrant remains, the struggle shall continue.”

My maiden encounter with this quote came through a paper titled, Haidar ‘Ali and Tipu Sultan: Mysore’s Eighteenth-Century Rulers in Transition, written by Kavesh Yazdani. Being an explorer of the past, it appeared to be an important duty to investigate the source mentioned by Yazdani for making such a grandiose claim. He had referred to Secret Correspondence of Tipu Sultan edited by Kabir Kausar with a complete section called “Tipu’s Views on the American Declaration of Independence”.

Interestingly, Kabir’s source is The Sword of Tipu Sultan, a historical fiction by Gidwani. Isn’t it highly cynical that one of the most “seriously considered” academic non-fiction works relies on a historical fiction to build a narrative on how Tipu Sultan “drew inspiration out of the American War of Independence”? More interestingly, the Foreword to Secret Correspondence of Tipu Sultan was written by eminent historian B.R. Grover of Jamia Millia. Read the interesting point he observes as below:

“Compiled by an archivist in his methodical and scientific approach, this work is a welcome addition to the source material of the late 18th century history of India. It affords fresh ground for an assessment of the character and activities of Tipu Sultan and his place in history.”

The then director of the Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR), Grover goes on to laud this work for its “methodical and scientific approach”, even though it relies on a work of fiction—The Sword of Tipu Sultan—to make a hyperbolic claim about Tipu Sultan. Grover further recommends everyone to read this book!

Now let’s analyse the three points on which Tipu Sultan is glorified.

Tipu Sultan a freedom-fighter?

Wouldn’t it be best to again pick the most popular work used by most to idolise Tipu Sultan as a freedom fighter? Hence, I pick an anthology of essays, titled Confronting Colonialism: Resistance and Modernisation under Haidar Ali and Tipu Sultan, edited by eminent historian Irfan Habib. As the title itself suggests, the author attempts to project the two as the flag-bearers of modernisation and crusaders against colonialism. Ironically, there are innumerable primary sources that speak aloud of how Tipu Sultan had colonised the southern belt through the sword of Islam. This essay is not intended to deal with colonisation and atrocity under Tipu Sultan, I will just leave the readers with the verse mentioned on his sword which reads as below:

“My victorious sabre is lightning for the destruction of the unbelievers. Haidar, the Lord of the Faith, is victorious for my advantage. And, moreover, he destroyed the wicked race who were unbelievers. Praise be to him, who is the Lord of the Worlds! Thou art our Lord, support us against the people who are unbelievers. He to whom the Lord giveth victory prevails over all (mankind). Oh Lord, make him victorious, who promoteth the faith of Muhammad. Confound him, who refuseth the faith of Muhammad; and withhold us from those who are so inclined. The Lord is predominant over his own works. Victory and conquest are from the Almighty. Bring happy tidings, Oh Muhammad, to the faithful; for God is the kind protector and is the most merciful of the merciful. If God assists thee, thou wilt prosper. May the Lord God assist thee, Oh Muhammad, with mighty victory.

Let us now inspect how well Haidar Ali and Tipu Sultan stood against colonialism.

On the issue of Tipu Sultan taking on the British, we need to understand that all he was trying to do was to safeguard his Islamic influence over the land he was ruling. A serious student of history would go back to the contemporary source of that period to get to the truth. I came across The Asiatic Annual Register for the year 1799, and the details on Page No. 194-95 under title “Supplement to the Chronicle” contained the thing of interest pertaining to the subject. It tells us that in February 1797, the captain of a French ship, François Ripaud, dismasted in Mangalore.

He was a conman who exemplified himself as the second-in-command in Mauritius and reflected as authorised personality to discuss Mysore’s succour with a French force that had already amassed to expel the British from India. Tipu fell for this. There began his tourney of French correspondences. It was on the second day of April 1797, when he gave his complete proposal to the French authorities through a letter. It contained among other things the proposal to replace the British with the French, and the equal division of property and territory between the French and him. We also get to know that Tipu was set to hand over Goa and Bombay to new allies, thereby replacing English with French. Irfan Habib should let us know if the proposal to replace one coloniser by another makes Tipu anti-colonial?

One can also look at Tipu’s letter to Zaman Shah, the ruler of Afghanistan on the fifth day of February 1797. In the letter, he proposed jihad against the kafirs with intent to “free the region of Hindustan from the corruption by the enemies of Islam”. The action plan was as below:

- Zaman Shah was to banish the Marathas from Delhi.

- Next the collaborated Afghan and Tipu’s army would crush the Maratha power in Deccan.

This same strategy was being applied during the Khilafat Movement too. It has been documented clearly and unapologetically by Dr B.R. Ambedkar in his book Pakistan or the Partition of India. Dr Ambedkar writes as below:

“(…) when it is recalled that in 1919 the Indian Musalmans who were carrying on the Khilafat movement actually went to the length of inviting the Amir of Afghanistan to invade India (…)”

The communal Moplah outrage of 1921 in Malabar could be easily traced to the forcible mass conversion and related Islamic atrocities of Tipu Sultan during his cruel military regime from 1783 to 1792.

So, calling Tipu Sultan a freedom fighter is an outright insult to all the freedom fighters.

Tipu Sultan the pioneer of war rockets?

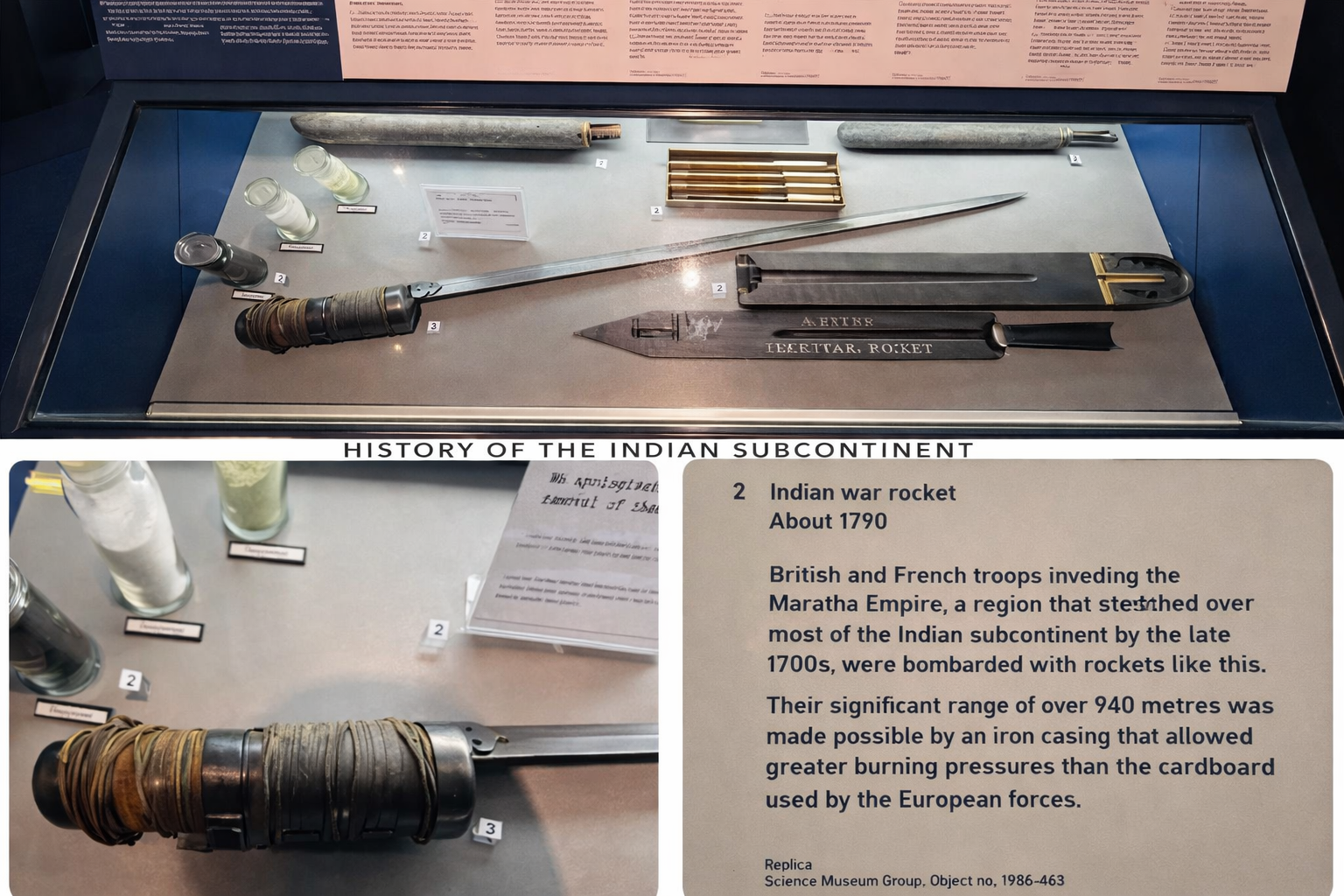

The other claim which is used to project Tipu Sultan as a man of science and technology was his “invention” of war rockets. But like the previous one, even this claim doesn’t hold much water; the primary sources say otherwise. As a first source I go back to the recorded experience of James Forbes (1749–1819). He writes in his book, Oriental Memoirs: A Narrative of Seventeen Years’ Residence in India, Vol. I:

“The war rocket used by the Mahrattas which very often annoyed us, is composed of an iron tube eight or ten inches long and nearly two inches in diameter. This destructive weapon is sometimes fixed to a rod iron, sometimes to a straight two-edged sword, but most commonly to a strong bamboo cane four or five feet long with an iron spike projecting beyond the tube to this rod or staff, the tube filled with combustible materials (…)”

The below images show the replica of Indian war rockets (1790) kept in London Museum of Science. The text clearly mentions Marathas using it against the Europeans.

Hence the attribution to Tipu Sultan to having led the creation of war rockets is a shaky assertion. There are even more primary sources which contradict any such assertion.

Tipu Sultan supported temples and maths, Marathas looted them?

Even this claim reflects how ill-informed people are about what the primary sources say. The usual narrative goes like this: That Marathas destroyed a math that was given grants by Tipu Sultan. Let’s verify it.

The Sringeri Math was sacked by the Pindaris, the freebooter mercenaries who had nothing to do with the Maratha instructions. According to A.K. Shastry, the editor of The Records of the Sringeri Dharmasamsthana:

“However, Peshwa Madhavrao Narayan conducted an enquiry & ordered Parasuram Bhau to give compensation & return the looted articles to the Matha. Parsuram gave a positive reply (Kd. 129, R. 52 in Marathi). The Peshwa’s letter reveals his key interest in giving compensation to the Matha. The positive reply from Parasuram Bhau to the Peshwa would form an impression that the foolish plunder of Sringeri was not due to any deliberate intention on his part, but a result of the predatory habits of the Pindaris in his contingent.”

It becomes very clear from the math’s record that Marathas never intended to do what the Pindaris had done and had even accepted to compensate despite this not being their own instruction. The same record also tells us that Tipu was donating to the math, but some observations give an interesting perspective. Read this excerpt from History of Raja Kesavadas by V.R. Parameswaran Pillai:

“With respect to the much-published land-grants I had explained the reasons about 40 years back. Tipu had immense faith in astrological predictions. It was to become an emperor (padushah) after destroying the might of the British that Tipu resorted to land-grants and other donations to Hindu temples in Mysore including Sringeri Mutt, as per the advice of the local Brahmin astrologers. Most of these were done after his defeat in 1791 and the humiliating Srirangapatanam Treaty in 1792. These grants were not done out of respect or love for Hindus or Hindu religion but for becoming Padushah as predicted by the astrologers.”

Alas! He is the same Tipu who had butchered thousands of Hindus and Christians, done forcible circumcisions, destroyed multiple temples and churches, commissioned literature to incite jihad against non-Muslims, forcibly took non-Muslim women to his harems, etc. How naive it is to believe that the bigoted tyrant was sorrowful for Shankaracharya’s math being looted by some freebooters!

Some interesting nodes to be dealt with later

As I look for the source from where these fake narratives emerge, it takes me to a paper Aurangzeb and Tipu Sultan by B.N. Pandey which talks of Tipu giving grants to 156 Hindu Temples. Pandey writes, “Prof. Srikantiah supplied me with the list of 156 temples to which Tipu Sultan used to pay annual gifts.”

Then we are told that Sir Brijendra Nath Seal, the then vice-chancellor of Mysore University, had forwarded Pandey’s letter to Prof. Srikantiah and the latter responded by giving this list.

Interestingly, Sir Seal was the VC of the Mysore University between 1921 and 1929. Any person with common sense would tell that Pandey must have received this list in or before 1929, but it took him 64 years to make this information public; Pandey mentioned it for the first time in his lecture on Tipu on 18 November 1993!

Another source of misinformation is B.A. Saletore’s article, “Tipu Sultan as Defender of the Hindu Dharma”, was first published in 1999 (Medieval India Quarterly, Vol. I, No. 1) It is reprinted in Confronting Colonialism (pages 115-30). This article begins itself with a Kannada sanad issued with Tipu’s seal. It talks about a dispute regarding worshipping at a mandir in Mysore, where Tipu is said to have not only given remedies to the injustice done by his own official, but he also rectifies an omission made by a previous Hindu ruler of Mysore.

In this case too, truth seems miles away. Saletore says, “The second line of the sanad contains merely the Hindu cyclic year and the month and the day (Siddhartha saum. Bhadrapada ba. 5) which corresponds to 15 September 1783.” Here is the error. The cyclic year Siddhartha occurred only once during Tipu’s life which corresponds with Saka year 1721. Bhadrapada Badi 5 of the year named Siddhartha, Saka year 1721 corresponds with 19 September 1799, and Tipu had died on 4 May 1799 (138 days before the sanad is stated).

There is a long list of errors around each document that is used to glorify Tipu. Perhaps, I will pick each one in separate essays anytime soon. – Firstpost, 1 April 2022

› Aabhas Maldahiyar is an author, architect and historian.

Read Online

- Tipu Sultan: The Tyrant of Mysore – Sandeep Balakrishna

- How brave was Tipu Sultan really? – Sanbeer Singh Ranhotra

- Tipu Sultan, Adolf Hitler and religious tolerance – Balbir Punj

- Tipu Sultan: Common icon of Pakistan and Congress – Balbir Punj

- Tipu Sultan was no freedom fighter – R. Sampath

- Tipu Sultan Jayanti is needless spectacle: Karnataka HC – M.A. Deviah

- Tipu Sultan: The Aurangzeb of South India – Sandeep Balakrishna