The notion that the British Empire abolished slavery across most of the world is, in reality, a myth. What the Empire simply did was quickly devise an alternative means of reintroducing slavery, by terming it as ‘indentured labour’ across its colonies, and that sounded politically correct and socially more acceptable to the white Western world. – Monidipa Bose Dey

A post on X by Elon Musk, stating that “the British Empire was the driving force behind ending the vast majority of global slavery,” brought forth a great deal of outrage from his Indian readers, and rightfully so. Slavery, which was officially abolished in the British colonies on August 28, 1833, with the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act, created severe labour shortages in British-ruled plantation islands, as newly freed former slaves refused to work for the meagre wages offered at the time.

This shortage compelled the British Empire, under pressure from wealthy white planters, to find a politically acceptable alternative for obtaining “unfree labour” from the native populations in British colonies such as India. Consequently, the indentured labour system was introduced, with clauses such as “restrictions on freedom of movement”, penalties for “negligence”, “absence from work” being made into criminal offences.

Thus, indentured labour was nothing but “slavery with a contract”. The notion that the British Empire abolished slavery across most of the world is, in reality, a myth. What the Empire simply did was quickly devise an alternative means of reintroducing slavery, by terming it as “indentured labour” across its colonies, and that sounded politically correct and socially more acceptable to the white Western world.

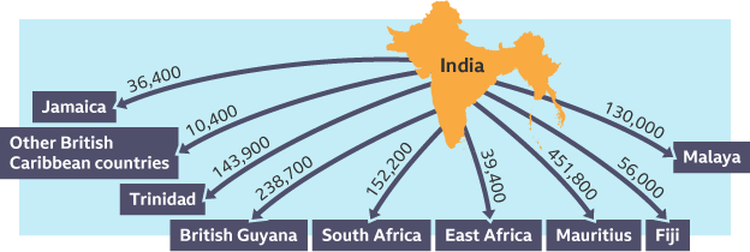

Owing to the numerous territorial conquests by Britain during this period, the British Empire liberally utilised its colonies as both sources and destinations for indentured labour. The primary destinations for Indian indentured labour were the British colonies of Trinidad, Mauritius, and British Guyana.

A brief overview of the European slave trade in India before the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833

The arrival of Europeans in India during the 17th century introduced a new dimension to the already thriving slave market under Islamic rulers. European powers entered the slave trade in the early 17th century, sourcing war captives from raids and conquests carried out by Arakanese rulers in the Bay of Bengal region. These raids created a systematic network of kidnappings, with countless Bengalis being captured and sold, turning ports such as Arakan, Chittagong, Hooghly, and Tamluk into infamous slave markets.

By the 1620s, the Arakanese were supplying over 1,000 slaves annually to the Dutch market. Not to be outdone, the Portuguese began conducting their own slave raids, targeting settlements along the Ganga belt. However, these activities soon drew the attention of the Mughals. By the mid-17th century, the Dutch were accused of illegally trafficking around 5,000 Bengalis annually to Batavia. Consequently, by the 1660s, the Arakan-Bengal slave trade was brought to a halt.

However, as the Bengal source of slaves dried up, another alternative supply of labour emerged, which provided irregular yet large numbers of more compliant Indian labour from both north and south India for European factories. Famines and wars led to the self-selling or “voluntary” sale of many adults and children, who were desperate to save themselves from starvation. The purchase of slaves of this kind is historically documented in Odisha, Bengal, Thanjavur, Madurai, and Chingleput, and this continued for the next two centuries.

One documented slave purchase took place in 1622, after a prolonged drought (1618–20), when the Dutch bought 1,000 slaves on the Coromandel Coast and sent them to work in Banda and Batavia.

In cases of local wars, entire families were often sold, and between 1658 and 1662, more than 7,000 slaves were bought and sent to Sri Lanka. In the 1670s, a prolonged period of crop failures led to large-scale slave sales from Tuticorin, with slaves being sent to Sri Lanka and Batavia. Indian slaves were also exported to the Dutch colonies in South-East Asia. In the first half of the 17th century, besides the Dutch, Danish, and Portuguese, English traders were also heavily involved in the slave trade, sending Indian slaves from these regions to work on rice and pepper plantations in various foreign destinations. In the latter half of the 17th century, English slave traders also shipped slaves from the port of Madras.

In the 18th century, India saw a rising number of political instabilities, armed conflicts, general financial mismanagement by the ruling classes, and increasing taxes. All these factors combined to create the horrific Bengal famine of 1770, which wiped out almost one-third of the population of Bengal. As the value of money fell, an overall decline in living standards led to an increasing outward flow of labour.

Additionally, as Indian political control over the ports weakened, slave markets began thriving around European colonial settlements. By the second half of the 18th century, French and Dutch colonies were taking in large numbers of Indian slaves, particularly when a series of famines struck eastern India.

In 1785, after a crop failure, many children were put up for sale, and the Collector of Dhaka reported seeing boats “loaded with children of all ages.” A few years later, Lord Cornwallis wrote, “Hardly a man or woman exists in a corner of this populous town [Calcutta] who hath not at least one slave child … most of them were stolen from their parents or bought for perhaps a measure of rice, in times of scarcity.”

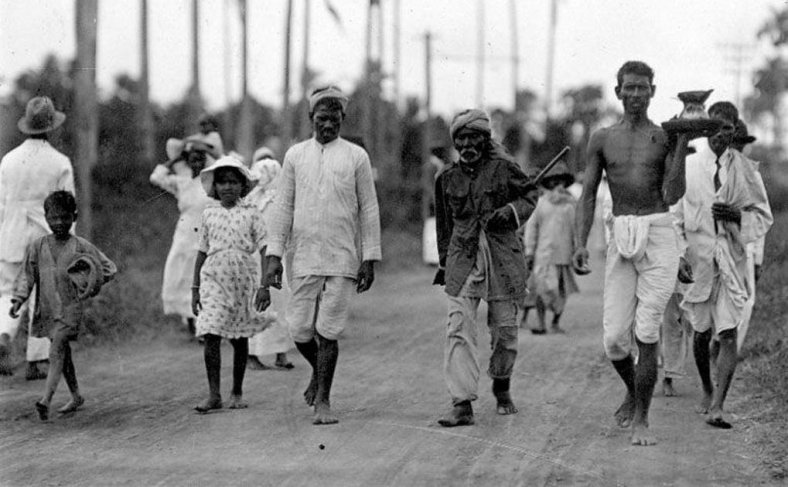

Those exported as slaves often included nomadic farmers, poor labouring classes, or aboriginal people known as “Hill Coolies” or “dhangurs”. These people were chosen based on their being young, active, and able-bodied. Most were unaware of where they were being sent, the nature of the work they would undertake, or the length of their journey.

Bowing to pressure from the abolitionists back home in Britain, by the end of the 18th century, the British were forced to start seizing ships carrying slaves, even though their main focus was on the ships of their trading enemies (Dutch and Portuguese); and the Slavery Abolition Act was passed in 1833. However, soon after the 1833 Act was passed, a solution to the labour crisis in colonial plantations arising from the abolishment of slavery was chalked out. Indians were turned into “indentured labourers” by British policymakers and exported to their sugar colonies under the new indenture system.

After the abolition of slavery

After the abolition of slavery in 1833, plantation owners explored various options for procuring labour, including sourcing workers from Africa, Canada, Europe, and China, but none of these proved viable. These failures turned the Empire’s attention to India as a long-term and reliable source of labour, and in the 19th century, India became the primary supplier of labour to the sugar colonies across the British Empire. As noted by the Royal Commission of Labour in 1892, the “importation of East Indian coolies did much to rescue the sugar industry from bankruptcy.”

The Indian indenture system was entirely state-controlled and involved a written and so-called “voluntary” contract (an “agreement,” also known as Girmitiyas in Fiji), which emigrants signed or provided a thumbprint for before leaving India. While the contract contained certain protective clauses for the workers, there were significant disparities between the rhetoric given in the contract paper and the ground realities on the plantations. There were innumerable reports of fraud and the use of force during the recruitment and transportation of labourers, as well as the appalling conditions under which Indian workers were forced to labour on the plantations.

A look at the indenturing process of labour from India reveals considerable evidence of the harsh treatment meted out to the indentured workers. In Jamaica, an ordinance fixed the wage rates at one shilling per working day (9 hours) for adult males, and 9 pence for women and children; however, the actual wages paid were much lower (around 10 pence for adult males). New labourers were provided with rations free of charge for the first three months, but the cost of the rations was later deducted from their already meagre wages. Wages were so low that the labourers could hardly make any savings, and furthermore, indentured labourers were not allowed to earn extra income. Absence from work was dealt with harshly by most employers. The harsh working conditions faced by the indentured labourers in Jamaica were evident in the high suicide rates among them. Death rates from tuberculosis and malaria were also high. Similar harsh conditions prevailed in Mauritius and Demerara, while in Trinidad, indentured labourers from India faced additional racial biases, being labelled as barbarians, pagans, and so on.

Conclusion

Thus, similar to slavery, the use of indentured labour in colonial plantations remained a process of extracting maximum profits by reducing transportation costs and keeping wages at a bare minimum. Additionally, wages were deducted for taking leave from work or for other work-related negligence, with imprisonment sometimes awarded for such offences. In this way, indentured labour was nothing but slavery with a written contract that claimed the workers had agreed to all the terms and conditions.

The use of indentured labour from colonies like India to serve the British Empire’s trade and financial interests in the 19th and 20th centuries tells a story of uneven power dynamics between the labourers from the colonies and the profits flowing into the ruling country. Supplying indentured labour from India provided additional benefits, enabling maximum profit extraction by employing workers in plantations under near-slave conditions, with little compensation for their extremely hard work and harsh living conditions. – News18, 23 Novemeber 2024

› Monidipa Bose Dey is a well-known travel and heritage writer.