Goel defined the three main threats to Sanatana Dharma—political Islamism, proselytising Christianity, and anti-national Marxist-Leninism. It has taken over 40 years, without adequate credit, for his ideas to be mainstreamed. – Makarand R. Paranjape

1 – The wronged man who turned right

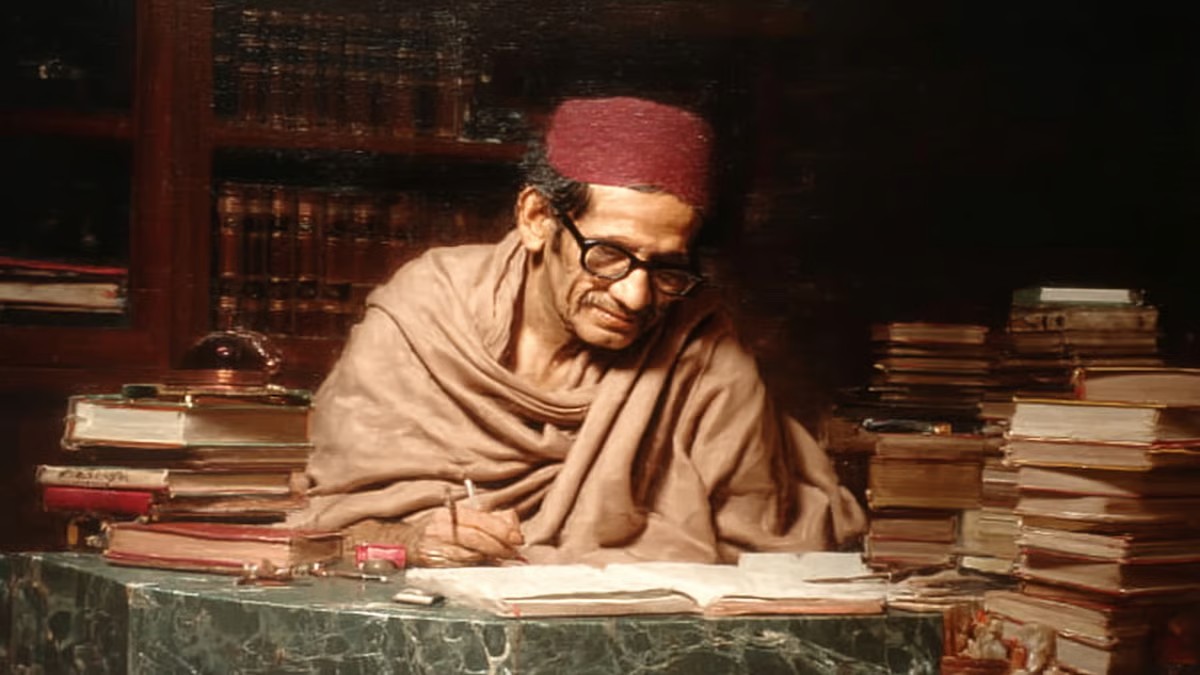

On October 16, 2024 India ought to be marking the 103rd birth anniversary of one of our greatest, but still least recognised, post-independence intellectuals. The one who almost single-handedly created an enormous and powerful body of work against the “history men” and “eminent historians.” But he was not even recognised as a historian. Indeed, he was never a part of the academy. He carried out his lonely crusade from outside the safety and comforts of well-funded and influential institutions. The establishment tried to erase him by what has famously come to be called “strangling by silence”.

Who was he? His name is Sita Ram Goel. It may ring a bell in the minds of some, but his huge and impressive body of work remains mostly unknown among the thinking and reading public. Today, this name is bandied about freely in right-wing circles. There are even courses being taught on him. Suddenly, we notice many champions and followers of his line of thinking. But none of them, as far as I know, has engaged with his work in depth. Most of the secondary material is informative and ideological, characterised by borrowed plumes and virtue signalling. The only volume I know on his work that makes a worthwhile contribution has not even been edited by an Indian. It is the work of the redoubtable and indefatigable Koenraad Elst. Who has also been strangulated by silence.

Indeed, “right-wing” India, despite being in power for over 15 years at the Centre and much longer in several states, is yet to produce scholars who, far from matching Goel’s competence or persistence, have even bothered to engage seriously with his oeuvre. Despite massive government, institutional, and private funding. In the meanwhile, we must be content with fiery, even incendiary, expositions such as appear frequently on web platforms like the Dharma Dispatch.

Goel was born in a Vaishnava Bania Agarwal community in the Chhara village of present-day Haryana. His own family tradition was based on the Granth Sahib of Sant Garibdas (1717-1778). But by the time he was 22, he says, “I had become a Marxist and a militant atheist. I had come to believe that Hindu scriptures should be burnt in a bonfire if India was to be saved.” He also became an Arya Samaji and, then, Gandhian before turning seriously to Marxism. Living in Calcutta, where his father worked in the jute business, such an attraction and affinity was natural.

Elst’s eponymous opening chapter, “India’s Only Communalist,” eloquently spells out the extraordinarily uncompromising and exceedingly courageous challenge that Goel posed to what was akin to India’s prevailing state religion—Nehruvian secularism. Goel called it a “perversion of India’s political parlance”, in fact, nothing short of rashtradroha, or treason. In that sense, he was India’s only true communalist. For everyone else, RSS and VHP included, were tying themselves into knots to prove how truly secular they were—and still are.

It was Goel who spelled out clearly that what went by the name of secularism was actually what Elst has termed negationism. The denial of the life-and-death civilisational, religious, spiritual—and, yes, secular— conflict between a conquering Islam and a resistant Hindu society. Nehruvian secularism, to Goel, was not only an attempt to whitewash this horrifying history of Islamic conquest, vandalism, plunder, conversion, and genocide, but it was also the continuous appeasement of a Muslim minority in India till it held the Indian state and the Hindu majority to ransom.

Despite his early commitment, Goel’s disillusionment with the Communist Party of India (CPI) was triggered by their support of the Muslim League in its demand for a Muslim state of Pakistan. Goel himself, along with his family, narrowly missed the murderous Muslim mob fury of Direct Action Day during the great Calcutta killings of August 16, 1946. Independence came exactly a year later, with Goel on the verge of joining CPI. But the Communists took a belligerent stance against the Indian government, calling for an armed revolution. Consequently, Nehru banned the CPI in 1948. In the meanwhile, Goel’s intellectual mentor and the major influence on his life, Ram Swarup, himself a rising intellectual, weaned him forever from Communism.

Goel soon turned 180 degrees into one of India’s prominent anti-Communists, actively working for the Society for the Defence of Freedom in Asia. Several of his early works warned of the dangers of Communism, both the Soviet kind and, closer home, of Red China under Mao Zedong. Ram Swarup fired the first salvos, publishing the pamphlet Let Us Fight the Communist Menace in 1948, following it up Russian Imperialism: How to Stop It (1950). Then it was Sita Ram Goel’s turn. His amazingly prolific output in the 1950s include: World Conquest in Instalments (1952); The China Debate: Whom Shall We Believe? (1953); Mind Murder in Mao-land (1953); China is Red with Peasants’ Blood (1953); Red Brother or Yellow Slave? (1953); Communist Party of China: a Study in Treason (1953); Conquest of China by Mao Tse-tung (1954); Netaji and the CPI (1955); and CPI Conspire for Civil War (1955).

The Communist threat, looming large after the occupation of Tibet, materialised in China’s invasion of India in 1962.

The war lasted barely a month. Chinese troops of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) crossed the McMahon Line on October 20. After capturing an area the size of Switzerland, some 43,000 square kilometres in Aksai Chin, they declared a ceasefire on November 21. Nehru was a broken man. He died less than two years later, on May 27, 1964, his dreams of a united Asian front against global capitalism shattered. The border standoff still continues with over 20,000 Indian and 80,000 Chinese troops massed on either side, with periodic skirmishes and casualties.

Goel was proven right; Nehru was wrong. Yet, during the Chinese aggression against India, quite ironically, established Leftists and highly placed bureaucrats, including P.N. Haksar, Nurul Hasan, I.K. Gujral, called for Goel’s arrest. During the 1950s, Goel wrote over 35 books, of which 18 were in Hindi. He also translated six books. He stood for elections from the Khajuraho constituency as an independent candidate in the 1957 Lok Sabha elections—but lost. He then embarked upon a publishing programme upon the suggestion of Eknath Ranade of RSS. However, according to Elst, RSS refused to sell or promote his books after the initial encouragement.

In 1957, Goel moved to Delhi, taking up employment with the Indian Cooperative Union (ICU) started by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay. But Goel’s attack on Communists, both of the Chinese and Soviet Union varieties, had made him many enemies.

Goel, instead, trained his guns on Nehru, whose deep Communist sympathies and miscalculations had cost India so dear. He had been criticising Nehru in a series in the RSS mouthpiece, Organiser, under the pseudonym Ekaki (Alone). In 1963, he published these with the provocative title, In Defence of Comrade Krishna Menon. Why? Because V.K. Krishna Menon, as defence minister, had not only presided over India’s debacle but had also been an avowed Communist and Nehru favourite. In supposedly defending him, Goel traced the malaise back to Nehru himself, as a confirmed Fabian Socialist and consistent supporter of Leftist regimes across the world. As a result of this open attack, Goel lost his job in the state-funded ICU.

Jobless and free to pursue his own interests full-time, Goel went into publishing himself. In 1963, he started Biblia Impex, a book publication, distribution and import-export business. Apart from his own and Ram Swarup’s books, he also published Dharampal’s Indian Science and Technology in the Eighteenth Century and The Beautiful Tree. Later, in 1981, Goel also founded Voice of India (VOI), a non-profit publishing house, dedicated to the defence of Hindu society. VOI still continues with his grandson, Aditya Goel, at its helm. It has published over hundred titles in the ideological defence of Hindu society. – Open Magazine, 11 October 2024

2 – The unsung scholar extraordinaire

The threat of Communism’s taking over India receded after the hugely unpopular Chinese invasion. The Communist Party of India itself split into two, one section affiliated with the Soviet Union, and the other with Maoist China. Sita Ram Goel now turned his attention to the Hindu-Muslim fault line that had divided India for centuries. It was an unhealing wound that needed the nation’s urgent attention. Instead, we were in constant denial, eager to erase the fact that Hindu society had endured an existential threat under two waves of colonialism, Islamist and Western.

Hindu secularists and Leftists tried almost obsessively to blur the theological and civilisational line between the invading and colonising Islamic empires and Hindu society. They come up with all kinds of artifices and subterfuges, including mile-jule sanskriti, Ganga-Jamuni tahzeeb, aman ki asha, and so on. Commenting on Sita Ram Goel’s work, Koenraad Elst explains this almost suicidal folly: “Contrary to the fog-blowing of the secularists and their loudspeakers in Western academe, who always try to blur the lines between Hinduism and Islam, a line laid out ever so clearly by Islamic doctrine, Goel firmly stuck to the facts: Islam had waged a declared war against infidelism in India since its first naval invasion in AD 636 and continuing to the present.”

This line so openly and clearly drawn between Muslims and non-Muslims by both the precepts and practice of Islam through the ages confronts us in every conflict situation. It turned into a bloody conflagration during and after the Partition. It still simmers as an incarnadine boundary between India and its Muslim neighbours. The latter born, as we are never tired of repeating, of the same stock as the Hindus. It was Goel who first enunciated with the greatest clarity that India had been subjected to two waves of colonialism, Western, and prior to that, Islamic. His classic exposition of the latter, The Story of Islamic Imperialism in India (Voice of India, 1994), should be compulsory reading in every course on post-colonialism. Instead, it is erased altogether.

That is why Goel focused his energies on the breaking-India efforts of the two Abrahamic and adversarial faiths which, to him, were the greatest threats to Hindu society, Islam and Christianity. Not as religions per se but as religious and political ideologies. Christianity worked against the native populace through the well-organised and funded enterprise of conversion. The difficulty with Islam was much deeper and historical. The unresolved conflict between a conquering Islam and a resistant Hindu society led not only to India’s Partition on religious lines, but also to continuing violence, riots, appeasement, and separatism within the country.

The decisive shift in Goel’s intellectual career occurred in 1981 when he retired from his mainline book business and created the non-profit Voice of India publishing platform. His aim, as stated in an early book from that period, Hindu Society Under Siege (1981), was to define the three main threats to Sanatana Dharma—political Islamism, proselytising Christianity, and anti-national Marxist-Leninism. As Elst puts it, “The avowed objective of each of these three world-conquering movements, with their massive resources, is diagnosed as the replacement of Hinduism by their own ideology, or in effect: the destruction of Hinduism” (ibid). It has taken over 40 years, without adequate credit, for his ideas to be mainstreamed. But today they have become commonplace, on the minds and tongues of most right-wing or Hindutva intellectuals and activists. Only a few of them say them or think them through as well as he did. Worse, very few of them acknowledge—or even read—Goel’s works.

What is, however, noteworthy is how different Goel was from these latter-day crusaders in one important aspect. Though he believed that Mahatma Gandhi had misunderstood and underestimated the threat of political Islamism, Goel never denounced him as a British stooge, charlatan, father of Pakistan, let alone a paedophile. Nor, in fact, did he advocate a Savarkarite Hindutva. Goel’s position remained firmly liberal, rational, democratic, and spiritual. He never preached hatred toward or between communities, nor did he wish to demonise any group of citizens because of their religion or ethnicity. Instead, he was interested in truth-seeking and truth-telling, holding the state and the political class accountable to the first principles of the republic, not playing havoc with the future of the nation with appeasement, favouritism, or identity politics.

Readers, especially those who are quick to typecast the right-wing, would be surprised to know that he had quite a few run-ins with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its affiliates, though he was sympathetic, overall, to their role in Hindu character-building and nationalism. Though he wrote often for Organiser and Panchajanya, he often found the RSS outlook narrow-minded, not to speak of muddled. He accused them of confusion and double-speak, using the same tired and dishonest cliches about secularism and national integration which falsified both history and ground reality. Unlike them, Goel had the guts to call a spade a spade.

His astonishing output during this phase, which lasted right till the end of his days, borders on the incredible; he was an intellectual giant and his was a giant’s labour. It is not possible to engage seriously with his enormous output in these two pages, let alone do justice to it. Suffice it to say that there is enough published material by him to support several PhDs. Here is a list, drawn up by Elst, of his major writings. It does not include essays or chapters published in books edited by others or, indeed, the first Hindi translation of Taslima Nasreen’s Lajja, published in instalments in Panchajanya. I have already mentioned some of his works earlier, but a more detailed listing is salutary: Hindu Society Under Siege (1981, revised 1992); Story of Islamic Imperialism in India (1982); How I Became a Hindu (1982, enlarged 1993); Defence of Hindu Society (1983, revised 1987); The Emerging National Vision (1983); History of Heroic Hindu Resistance to Early Muslim Invaders (1984); Perversion of India’s Political Parlance (1984); Saikyularizm, Rashtradroha ka Dusra Nam (1985); Papacy, Its Doctrine and History (1986); Preface to The Calcutta Quran Petition by Chandmal Chopra (a collection of texts alleging a causal connection between communal violence and the contents of the Quran; 1986, enlarged 1987, and again 1999); Muslim Separatism, Causes and Consequences (1987); Foreword to Catholic Ashrams, Adapting and Adopting Hindu Dharma (a collection of polemical writings on Christian inculturation; 1988, enlarged 1994 with new subtitle: “Sannyasins or Swindlers?”); History of Hindu-Christian Encounters (1989, enlarged 1996); Hindu Temples, What Happened to Them (1990 vol 1; 1991 vol 2, enlarged 1993); Genesis and Growth of Nehruism (1993); Jesus Christ: An Artifice for Aggression (1994); Time for Stock-Taking (1997), a collection of articles critical of RSS and BJP; Preface to the reprint of Mathilda Joslyn Gage: Woman, Church and State (1997, ca. 1880), an early feminist critique of Christianity; Preface to Vindicated by Time: The Niyogi Committee Report (1998), a reprint of the official report on the missionaries’ methods of subversion and conversion (1955).

Though polemical, even provocative and pugilistic, each of these books is thoroughly researched and comprehensively argued. Very unlike today’s TV debaters and other credit-hogging activists who pretend that they have come up with “original” ideas and arguments which are already found in plenty of Goel’s writings. Without reading Goel or citing him, they repeat these ideas and arguments in a much worse and less persuasive manner. Indeed, the idea of the intellectual Kshatriya itself originates in Goel, though others now appropriate it as if they pioneered it. Thus, they end up doing injustice to Goel and a disservice to the cause that they profess to champion—performing the same U-turn manoeuvre that they condemn in others.

Mainstream academics and media, of course, continue completely to ignore Goel’s work. But Hindu organisations too, far from engaging with his massive output, also neglect to give him adequate credit. One might wonder why. In my view, the answer is simple. No one has Goel’s intellectual calibre, stamina, or capacity. In the prevailing anti-intellectual climate, politics, slogan-shouting, and ideological posturing become much easier to friend and foe alike. The skills required for reading, writing, research, exposition, analysis, and argument are sorely lacking in Indian society. Goel is a victim of this glaring deficit.

Moreover, during the heyday of his intellectual activism, there was no internet, Wikipedia, or Google Baba. Indians were so brainwashed by sarva dharma samabhava—regarding all religions equally—that they understood neither the basic texts or the intent of the two imperialistic Abrahamic faiths, Christianity and Islam. Goel acquainted a large body of naïve and mistaken members of the public with the historically verifiable theology and teleology of these proselytising faiths. Which was to exterminate Sanatana Dharma, as they had other Pagan traditions that they had encountered. Also, the naked admission of global conquest and dominance.

A posthumous Padma Award for Sita Ram Ji? That is the least we can do to honour the memory and legacy of this scholar extraordinaire. – Open Magazine, 25 October 2024

› Makarand R. Paranjape is an author, poet, a former director at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, and former professor of English at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.