In Congo, missionaries were not peripheral actors. They ran schools, hospitals, food distribution systems, and civil institutions. Access to education, safety, and even medicine was conditional on baptism. Indigenous belief systems were systematically destroyed. Local authority structures were dismantled. Traditional leadership was delegitimised. Submission replaced sovereignty. – Prosenjit Nath

For more than a century, a powerful civilisational myth has been sold to the world’s poorest societies: convert to Christianity, get educated, become modern, and eventually grow rich “like America.” It is a narrative aggressively promoted by missionaries, amplified by Western media, and internalised by post-colonial elites. Africa was told this story repeatedly. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is what happened next.

Today, over 95 per cent of Congolese identify as Christian. This has been the case for nearly a hundred years. Yet in 2026, the country remains among the poorest on earth. Its GDP per capita hovers between $800 and $900. More than 70 per cent of the population lives in extreme poverty. A staggering 97 per cent of children are unable to read and understand a simple text. This outcome is often framed as a “failure” of Christianity, as if the faith promised prosperity and somehow failed to deliver. Others blame “residual paganism” for the stagnation. Both framings are wrong.

Christian theology never promised wealth, material success, or worldly flourishing. In fact, it does the opposite. It elevates suffering, sanctifies poverty, warns against riches, and places salvation firmly outside this world. “Blessed are the poor,” not the prosperous. “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter heaven.” The Christian worldview sees deprivation not as a problem to be solved, but as a spiritual condition to be endured.

So what promised education, dignity, prosperity, and “development”? Not theology. It was missionary propaganda. Congo did not misunderstand Christianity. It was sold a claim Christianity never doctrinally made.

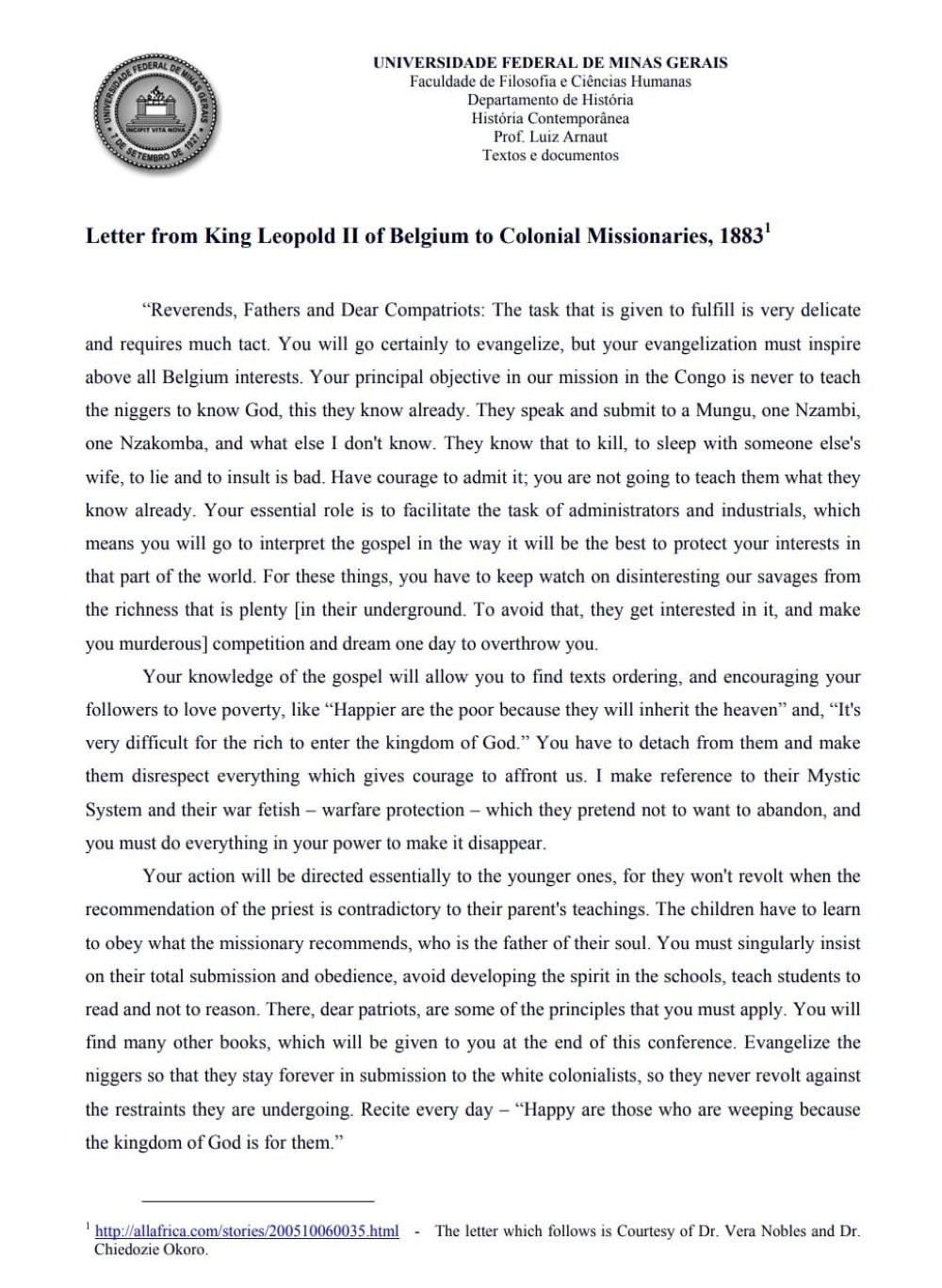

The Christian Experiment Began With A Gun

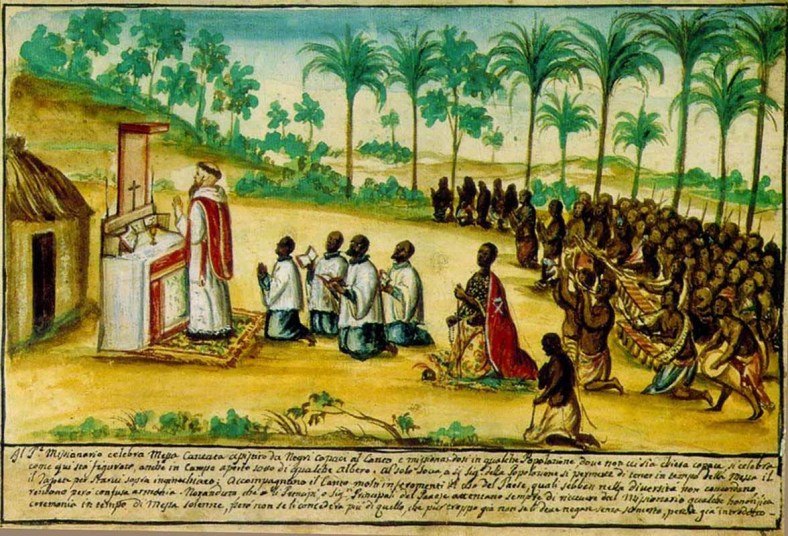

Christianity did not enter Congo peacefully. It arrived tied to the boot of King Leopold II of Belgium, a devout Christian monarch who ruled Congo as his personal colony. Under his regime, rubber quotas were enforced through terror. Failure to meet them meant mutilation. Severed hands were collected as proof of punishment. By conservative estimates, over 10 million Congolese died during this period.

This was not a deviation from Christian rule; it was its colonial expression. Churches were built alongside forced-labour camps. Priests blessed the system. The cross stood next to the whip.

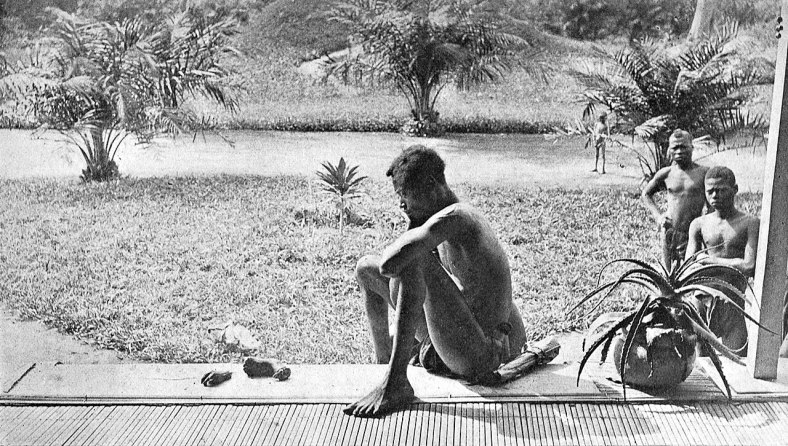

The most famous photograph from this era shows Nsala, a Congolese man staring at the severed hand and foot of his five-year-old daughter, cut off because his village failed to meet rubber quotas. Was this “Christian charity” at work? Was this civilisation? Or was it extraction disguised as salvation?

Missionaries Didn’t Just Preach, They Governed

In Congo, missionaries were not peripheral actors. They ran schools, hospitals, food distribution systems, and civil institutions. Access to education, safety, and even medicine was conditional on baptism. Indigenous belief systems were systematically destroyed. Local authority structures were dismantled. Traditional leadership was delegitimised. Submission replaced sovereignty.

The message was simple: abandon your gods, abandon your customs, abandon your identity, and you will be uplifted.

But after all that, did “Jesus save” Congo from disease, hunger, and poverty? No. The people complied, converted, and surrendered their civilisational backbone. What they received was dependency.

A society cannot stand upright when its cultural spine is removed. What replaced it was not empowerment but obedience. Not self-rule but subservience.

A Christian Nation Without Power

Congo today is a Christian nation without the ability to exploit others. And we are told that this is “true Christianity.” Europe and America, we are told, are rich not because of Christianity but because they deviated from it. So what happens when a country follows Christianity sincerely? Congo happens.

Despite being one of the most mineral-rich regions on earth, Congo remains desperately poor. It holds vast reserves of cobalt, copper, gold, and coltan—minerals essential for the global green economy. Yet Congolese children mine cobalt with their bare hands so Western electric cars can run clean. Seven million people are displaced. Over twenty-five million face chronic hunger.

Christian Congo did not colonise anyone. It did not enslave other societies. It followed the gospel of submission and patience. And it was stripped bare.

The Real Lesson

The failure is not that Christianity did not make Congo rich. It never promised to. The failure is that Congo was sold a lie that faith would deliver development. That baptism would bring dignity. That abandoning its civilisation would result in prosperity.

The West did not become rich because it was Christian. It became rich by colonising, extracting, and enslaving—often justified using Christian language. Congo followed the moral code, not the power code. And paid the price.

This is the uncomfortable truth: Christianity works very differently for the coloniser and the colonised. For the powerful, it is a tool. For the powerless, it is a chain disguised as comfort.

Congo is not a failure of faith. It is the outcome of believing a civilisational lie—a lie that told a people to kneel when they should have stood. – News18, 12 january 2026

› Prosenjit Nath is a technocrat, political analyst, and author. He pens national, geopolitical, and social issues.