What happened during this week 1,000 years ago was not a one-off assault by a greedy Central Asian despot who just incidentally happened to be Muslim. Mahmud’s destruction of Somnath set off a millennium-long assault on it by men who definitely had one thing in common apart from Islam: an animus towards the Jyotirlinga. – Reshmi Dasgupta

From January 6 to 9, 1026, the army of Mahmud of Ghazni lay siege to the wondrous temple of Somnath near the port city of Veraval. The defenders of the fortified shrine eventually could not repel the troops of the Central Asian invader and Somnath was captured. It was Mahmud’s 16th raid on India and loot was not the only target. Contemporary sources mention that Hindu merchants offered more money if he spared the idol; he refused and struck the first blow.

For that act, Mahmud earned the title “Butshikan” or idol-breaker, from an admiring Islamic world and his renown for the desecration of Somnath and other major Hindu temples in India persisted for centuries. Sultan Sikandar Shah earned the same Butshikan title in the 14th century for destroying temples in Kashmir in pursuance of the precepts of the Sufi preacher Mir Mohammad Hamadani. Even 600 years later, Aurangzeb appreciated Mahmud’s Islamic fervour.

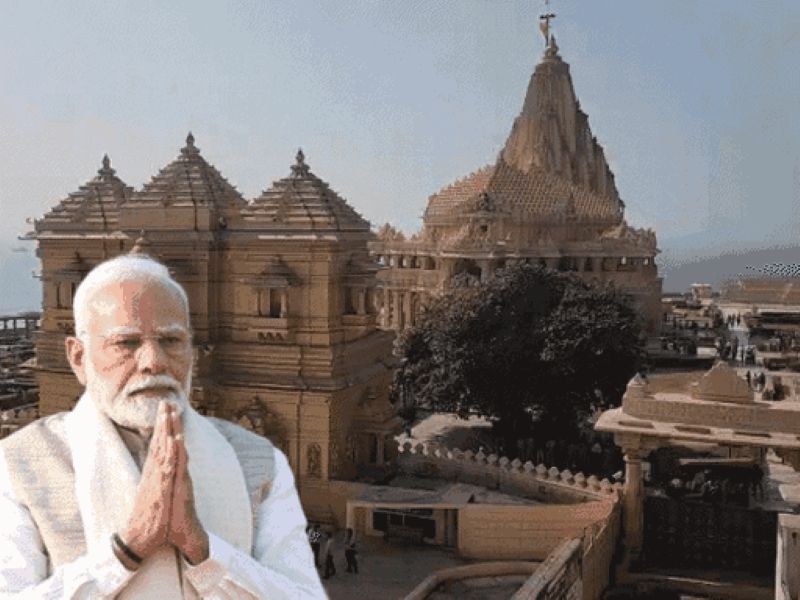

It is inevitable that Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s commemoration of the 1000th anniversary of the first destruction (as opposed to the misleading word “sacking” commonly used for the violent actions of Mahmud of Ghazni) of the Somnath temple will be countered with supposed “proof” of either “Arab” heroism or Hindu perfidy or both. It is now almost an article of faith among certain sections in India and abroad that Mahmud was more maligned than malevolent.

As has been often pointed out in recent times, the assertions of the high priestess of the secular camp Romila Thapar on the destruction of Somnath lack basis in actual facts even if delivered with withering condescension in impeccable upper class accented English. But there are plenty of willing believers in Thapar’s argument that Mahmud was not communal—merely venal—and that his destruction of the magnificent Shiva lingam at Somnath was incidental.

Indeed, the PM calling the repeated rebuilding of Somnath after each brutal destruction and plunder a symbol of the “unbreakable courage of countless children of Bharat Mata who protected our culture and civilisation” will be met with predictable counters. First, that “Arabs”—mainly traders who had settled in the area and married local women—died protecting Somnath from Mahmud’s marauders. Second, that there were many Hindus in Mahmud’s army.

There were indeed Hindus in Mahmud’s army, including battalion commanders, and he used them with varying effectiveness in campaigns on the subcontinent and even further north in Central Asia. But the phenomenon of mercenaries—soldiers of fortune who fight for the best paymaster—is well known. The presence of Hindus in his army cannot be taken to mean Mahmud was “secular” or that his actions were not intended to attack and diminish India’s majority faith.

There is no dependable account of Arabs dying while defending Somnath, but they could well have been miffed by their co-religionists from Ghazni disturbing their livelihoods. Arabs had all been Islamised by then although earlier traders and sailors may have adhered to pre-Islamic faiths including Christianity. So, it would be a stretch to imagine they would risk irking Allah by actually fighting alongside local Hindus kafirs to save Somnath from his holy warriors.

The Veraval Inscriptions (so named for the ancient port town next to the Somnath, which had a bustling mercantile trading business) dated to about 250 years after Mahmud’s destruction of the great Shiva lingam, highlight the dynamic between the two communities in the last millennium. The bilingual inscriptions from the reign of the Vaghela king Arjundev, records an agreement for the financing of the upkeep of a mosque at Somnath Patan built by a resident of Hormuz.

Curiously, the longer Sanskrit inscription lists the Hindu king and hierarchy but mendaciously describes the lord of the mosque as Vishwanatha and Shunyarupa and even calls Prophet Mohammed a “prabodhak” or preceptor. The Muslim shipowner donor from Hormuz Nuruddin Firoz is called a “dharmabandhav” of Sri Chhada who seems to be the mosque’s chief administrator. But in the shorter Arabic notation, there is no attempt to Indianise Allah or his Prophet.

The twin inscriptions seem to indicate that Hindu rulers bore no lasting animus against all Muslims—especially the Arab and Persian merchants from the Gulf—for the depredations of the Turkic invader from Ghazni 200 years before, and allowed them to set up mosques near the temple. But one sentence of the Arabic inscription points to the thinking of the Muslims even if they attempted to couch their initial outreach to the Hindus with seemingly syncretic gestures.

The Arabic inscription expresses the hope that Somnath will one day become a city of Islam, and that infidels and idols will eventually be banished from it. Why did the officials of the Vaghelas (the last Hindu kingdom of the region) allow that explicit expression of intent to pass unchallenged? Could they not read Arabic? Or were they persuaded, as indeed are some academics reading it 750 years later, that it was a “pro forma” statement and did not constitute a threat?In the event, though Somnath was revered enough for the 11th century Chalukya ruler Bhima I to rebuild it after Ghazni’s desecration, local inhabitants naively seemed to have borne no permanent suspicion of Muslims as the Veraval inscriptions two and a half centuries later seems to confirm. But a mere 35 years after those twin plaques were incised, the army of Delhi’s Sultan Alauddin Khilji under Ulugh Khan pillaged and destroyed Somnath yet again.

And that deed was approvingly chronicled by no less than the much-admired (even today) Persian poet Amir Khusro. In Khazain-ul-Futuh (Treasures of Victory), he gleefully wrote in 1310 (after Khilji’s armies attacked again in 1304 and annexed all of Gujarat):

“So the temple of Somnath was made to bow towards the Holy Mecca; and as the temple lowered its head and jumped into the sea, you may say that the building first said its prayers and then had a bath.”

He also added:

“It seemed as if the tongue of the imperial sword explained the meaning of the text: ‘So he (Abraham) broke them (the idols) into pieces except the chief of them, that haply they may return to it.’ A pagan country, the Mecca of the Infidels, now became the Medina of Islam. The followers of Abraham now acted as guides in place of the Brahman leaders. The robust-hearted true believers rigorously broke all idols and temples wherever they found them.”

Khusro also dispelled doubts about the intent of the Arabic Veraval inscription:

“Owing to the war, ‘takbir,’ and ‘shahadat’ was heard on every side; even the idols by their breaking affirmed the existence of God. In this ancient land of infidelity, the call to prayers rose so high that it was heard in Baghdad and Madain while the Khutba resounded in the dome of Abraham and over the water of Zamzam. The sword of Islam purified the land as the Sun purifies the earth.”

That Khusro described Somnath as the “Mecca of Infidels” underlines its primacy as a Hindu centre of worship, reiterating its pride of place as the first of the 12 Jyotirlingas listed in the Shiva Purana. So it is not surprising that every Muslim ruler thereafter who wanted to assert his religious cred and supremacy attacked Somnath, from Muzaffar Shah to Mahmud Begada to Aurangzeb. But it was restored, rebuilt, reconsecrated faithfully by Hindu rulers each time.

What is glossed over by apologists is that Somnath was not considerately left to resume worship. It was converted into a mosque by several Islamic attackers and then reconstructed repeatedly as a temple by Hindu monarchs. It was turned into a domed mosque by Aurangzeb in 1665. And the final rebuild happened in 1951, thanks to the determined efforts of Sardar Patel, KM Munshi and Dr Rajendra Prasad in the teeth of opposition from Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

In 1783, the formidable Maratha queen Ahilyabai Holkar had another Shiva temple constructed 200 metres from the original site of Somnath, whose added dome and minaret can be seen in late 19th century photographs now in the British Library. She had done the same three years earlier in Varanasi where the original Kashi Vishwanath temple had been mostly destroyed (only one wall left standing) and rebuilt as “Gyanvapi” mosque, also on Aurangzeb’s orders.

So, what happened during this week 1,000 years ago was not a one-off assault by a greedy Central Asian despot who just incidentally happened to be Muslim. Mahmud’s destruction of Somnath set off a millennium-long assault on it by men who definitely had one thing in common apart from Islam: an animus towards the Jyotirlinga. That it is standing proudly again is indeed a testament to the quiet determination and faith of the children of Bharat Mata, as PM Modi said. – News18, 7 January 2026

› Reshmi Dasgupta is a freelance writer formerly with the Times of India Group.