Wake up, folks, wake up! As intimidated as you are by the fear of going against the stream and looking racist, you don’t understand or don’t want to understand that a reverse crusade is on the march. As blinded as you are by the myopia and the stupidity of the politically correct, you don’t realise or don’t want to realise that a war of religion is being carried out. A war they call Jihad. A war which is conducted to destroy our civilisation, our way of living and dying, of praying or not praying, of eating and drinking and dressing and studying and enjoying life. As numbed as you are by the propaganda of the falsehood, you don’t put or do not want to put in your mind that if we do not defend ourselves, if we do not fight, the Jihad will win. It will win, yes, and destroy the world that somehow or other we have been able to build. – Oriana Fallaci in The Rage and the Pride

Violence does not live alone and is not capable of living alone: it is necessarily interwoven with falsehood. Between them lies the most intimate, the deepest of natural bonds. Violence finds its only refuge in falsehood, falsehood its only support in violence. Any man who has once acclaimed violence as his method must inexorably choose falsehood as his principle. – Alexander Solzhenitsyn in his 1970 Nobel lecture.

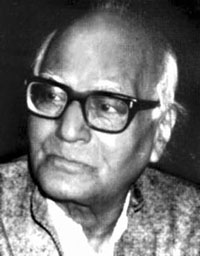

Writing against the current in a democratic society poses problems of a different kind. Pondering at the range and depth of writings of Ram Swarup (1920-1998) and Sita Ram Goel (1926-2003), and the approach of our academia and media towards them gives an inkling of the problem.

In a totalitarian political system—Fascist, Communist or Islamist—a non-conformist writer can hardly publish anything. Even writing in private is a dangerous venture. But in a country with complete freedom of speech, with a ‘politically correct’ intellectual ambience, an inconvenient author can be silently buried in indifference. Not even the most open minded readers would know of his existence. Speaking of the Soviet case, Solzhenitsyn had observed that “the environment is dense and sticky: it is incredibly difficult to make even the smallest movements because it immediately takes the environment with them.” In contrast, the atmosphere in democratic countries is “like a rarified gas, or almost a vacuum: there it is easy to wave one’s arms, jump, run, turn somersaults—but it all has no effect on anybody else, everyone else is doing exactly the same in a chaotic manner.”

Without understanding this difference, we can never comprehend why even sixty years’ of original work of the rare duo of Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel hardly left a mark on the intellectual scene of our country. Both died largely unsung. It is not a small measure of the regrettable situation that even a solitary biographical sketch of them each came from a Belgian scholar, Koenrad Elst. No Bharatiya scholar, journalist or student wrote one. Neither in their lifetime, nor after they passed away. Our media did not even bother to take note of the demise of Sita Ram Goel in 2003. The chief reason for this unfortunate state of affairs is that their work remained largely unknown to the general public of our country. Both were original and non-conformist thinkers. Our governments as well as the academic class felt quite at ease in ignoring them. Media happily followed suit.

There was a time in the Soviet Union when Solzhenitsyn was vilified. His works were considered ‘concoction’, ‘betrayal’, ‘disease’ and what have you. Even in the Soviet Literary Encyclopaedia of 1973 his name found no place at all (this, after he was already world-famous with Ivan Danisovich, and the Nobel Prize). He simply did not exist.

In this country, a very similar attitude was applied towards Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel as far as our academic class is concerned. Goel found no mention in intellectual debates and writings on issues he published for decades. If rarely someone mentioned his name, it was scornfully dismiss him as ‘communal’. Hence unwanted, irrelevant. It is a mark of the pathetic condition of our social sciences that after the demise of the Soviet Union, and opening up of the Soviet and East European archives, our Marxist professors were not dragged on the coals for their propagandistic writings masquerading as scholarly ones. Nothing happened by way of re-examining their highly distorted writings on history, political science or economics. On the contrary they are still ruling the roost! By corollary, even after the demise of communism, Sita Ram Goel and Ram Swarup are not accorded their due place in the scholarly arena for their realistic, incisive and farsighted analyses of the communist systems. Perhaps after the advent of a Saudi Gorbachev, this might be done.

Disaster at Inception: The English Takeover

Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel wrote on Communism, Marxism, Maoism, Islam, Christianity and Hindutva. In this country all these are politically sensitive subjects. As is well-known, to the first five issues it is considered politically correct to be respectful, even reverential. As for the last one, it is best to disregard, if not mock openly. Reasons are various for this pitiable situation in this otherwise intellectually rich country.

A misconception regarding the Islamic mentality on the part of the national leaders since the 1920s was one. Getting the very first prime minister heavily enamoured by Marxism, Soviets and Islam was another. It has to be understood that the founding moments of any institution, law or system invariably become crucial to set the tone and standards for a long time to come. For a free Bharat the period of, say, 1947-56 was such a founding one because so many of our intellectual or socio-political traditions laid down by the Communist-and-Islam-leaning first prime minister.

Jawaharlal Nehru: India’s First Prime Minister

English becoming the intellectual language of the country, even after freedom from the British rule, was the third reason. It summarily and effectively excluded more than 95% of the population from participating in influential intellectual exercises. Thus a possible corrective to ideologically marred theories, propositions etc was foreclosed at the very inception. English ensured that even if a Bharatiya citizen is wise, experienced, knowledgeable and articulate, he or she can do nothing to check or persuade an erring intellectual or a whole intellectual group—unless he can do it in English. Besides, he must also hold a high chair to be heard.

Discourse in any language other than English in this country, howsoever rich and invaluable, simply does not touch the influential, decision making classes. Thus, intellectual pursuits became an undeclared monopoly of a minuscule few, who, even if grossly errant, ignorant or misguided on a matter in hand, could still set the standards for the entire country to follow—history writing and NCERT textbooks since inception are a case in point. The rest of the population simply came to accept, in naïve belief, a la Soviet citizens of yore, that whatever is emanating from the high chairs of a council, academy, commission, university, centre or ministry is certainly better informed. “They must know better who speak and write in English” became the common, if disastrous, sentiment among the Bhartiya public.

In the subjects mentioned above, that never was the case. The philosophy, understanding and experiences of the common Bhartiya masses were vastly different from the English-wielding intellectual elite about, say, the ways of socio-economic change or the Islamic character. Yet they could do nothing, thanks to the monopoly of English in matters academic or policy, to correct the academic and political decision makers. This restrictive, anti-Bharat role of English in a free Bharat is hardly considered in analysing why such a “politically correct” intellectual atmosphere came to rule here.

Original Critiques of Islam, Christianity and Communism

In such a politically correct intellectual environment Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel jointly represented diametrically opposite views. The dominating political and intellectual classes which followed a different path, naturally detested this. It is, therefore, not surprising that the duo’s rich contribution was wholly ignored. Both started publishing their critical works with the advent of freedom in 1947. It is out of the purview of this essay to compare the parallel views of the duo and those of the ruling intellectual-political classes of our country. Suffice it to say that time has proven most of the analyses and conclusions of Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel right.

Of the nature and role of Marxism-Leninism, Soviet system, Maoist practice, and Communist economies, it is now irrefutably evident that whatever our first prime minister and Left-leaning economists, social scientists believed for decades (some still do) were indeed mere superstitions. As far the Islamic problem is concerned, anyone can judge the farsighted analyses the duo presented till the end of their lives. Life has shown, decade after decade, that from Gandhi to Atal Bihari Vajpayee, every leader or preacher seriously erred, with very tragic consequences, in assessing the Islamic problem. In their case, wishes were not horses. Every concession, every leniency, all hosannas to Islam did never bring a single positive result. As Sita Ram Goel put so succinctly, in one of his last contributions:

“A study of Hindu-Muslim relations since the foundation of the Indian National Congress in 1885 tells us that Muslims have been making demands—ideological, political, territorial—and Hindus conceding them all along. Yet the Muslim problem remains with us in as acute a form as ever. With the advent of petrodollars and the emergence of V.P. Singh, Laloo Prasad, Mulayam Singh and Kanshi Ram on the political scene, Muslims have become as aggressive and intransigent as in the pre-partition period.”

To understand the nature of the problems we are facing today on this score, and also to value the scholarly contribution of Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel, it would be helpful to see what some other gifted observers have concluded the world over. Oriana Fallaci, whom Milan Kundera calls the ideal of the 20th century journalism, has been saying this for the last twenty-five years. She is a remarkable writer inured to living with all races and habits and beliefs, accustomed to opposing any fascism and any intolerance without any taboos.

She is indignant towards all those who did not smell the bad smell of a war to come and who tolerated the abuses that “the sons of Allah” were committing in Europe with their terrorism. Her straight reasoning:

“What logic is there in respecting those who do not respect us? What dignity is there in defending their culture or supposed culture when they show contempt for ours?”

She puts the likes of Osama bin Laden on par with Hitler and Stalin, firmly arguing that fascism is not an ideology, but behaviour. She warns that the fight with this fascism “will be very tough. Unless we Europeans stop shitting in our pants and playing the double-game with the enemy, giving up our dignity. An opinion I respectfully offer to the Pope too.”

Do we comprehend what Fallaci is stating? Most of the members of our intellectual class would not. Let alone fighting a war, on the intellectual plane, they tend not even to see the international phenomenon and problem. As if every disaster perpetrated by the sons of Allah in any corner of the world is a mere accident and not manifestations of a single ideology.

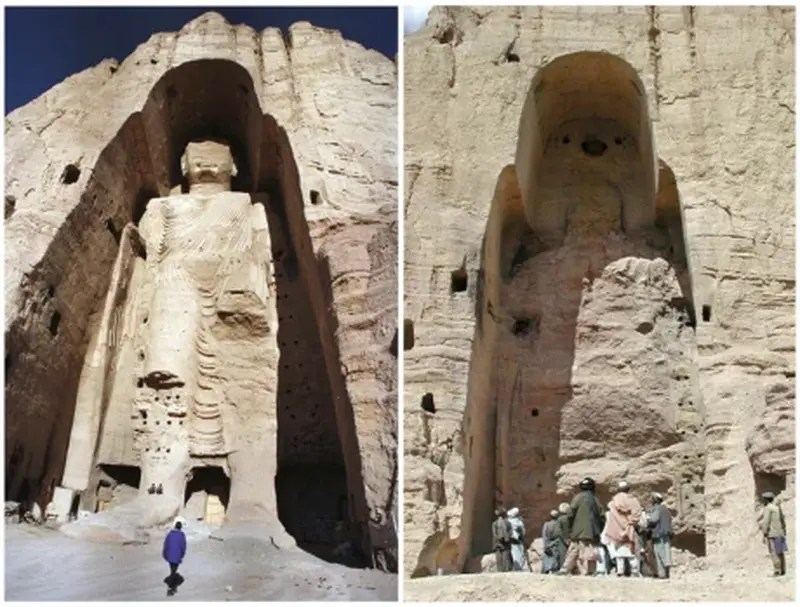

Bamiyan Buddha Destruction

Question: Why do some people remain unfazed even by violence of such magnitudes as 9/11, Bamiyan, Godhra or Nadimarg in Kashmir? They readily try to explain away such violence blaming some “primary” cause and thus shield the barbaric perpetrators. But the very same people hysterically cry “fascism” on even an ordinary statement that the Ayodhya temple movement is a national sentiment. Why such double standards?

Political correctness is not the whole answer. Love for one’s own comfort, ignorance and laziness also play the part for many a people. As Solzhenitsyn aptly said in the context of condemning the nuclear tests conducted by France and China, that the double standards were “not only because of moral squint, but simply out of cowardice. Because from an expedition into the Chinese desert or to the Chinese coast nobody would return—and they know it”. The same is truer of keeping silent on everything Islamic, fascist or terrorist, while crying hoarse about even non-acts of “Hindu fascism”. As the great author wrote, “They only protest when there is no danger to life, when the opponent can be expected to give in and when there is no risk of being condemned by ‘Leftist circles’—it is always better, of course, to protest with them.” This is highly apt to describe the noisy secularists of Bharat.

We have different scales of values for wickedness and punishment. According to one, killing of an innocent-looking terrorist—Ishrat Jahan for instance—or a missionary indulging in illegal proselytizing activities—Graham Staines—shatters the imagination and fills the newspaper columns with rage. While according to another, systematic cleansing of Hindus from the territory of Kashmir, Assam and Nagaland, burning an entire train coach with Hindu pilgrims in Godhra, mushrooming of Islamic terrorist dens in the border areas of West Bengal, Bihar and UP—all this gets no attention much less alarm. No condemnation, no seminar, no books, no documentation and, of course, no campaigns on the lines of “fight against saffronisation”.

Whenever an Islamic assault becomes impossible to ignore and at least our editorial classes feel compelled to write something of a criticism they never forget to mention “Hindu extremism” in the same vein. It is pure fiction, an added insult to meek Hindus who have been at the receiving end all along for centuries. No one speaks for them with force, with extra-constitutional methods. Hence no question of a Hindu “extremism”.

But in editorials, Islamic violence is never condemned on its own merit, it is wilfully clubbed with a Hindu one. This artificial balancing flies in the face of hard, horrible facts. There has never been a single act on the part of the Sangh Parivar which can even remotely match, either in words or deeds, those of the Islamic ones: Lashkar-e-Toiba, Student Islamic Movement of Bharat (SIMI), Deendar Anjuman, Hizb-ul-Muzahideen, Tablighi Jamat et al. Yet the politically correct editorial and academic classes of this country present Hindu “extremism” and Islamic terrorism on par. Worse, for some, the former is the cause of the latter. Therefore, the bigger culprit is the (Hindu) Sangh Parivar. Hence all fight is against “saffronisation” and none against “Islamisation” of every possible thing—land, people, culture, dress, food, language, thought and manners.

What kinds of scales are used in this artificial balancing of Islamic intolerance with an imaginary Hindu one? The first unit on one scale may be ten, but the first unit on another scale may be ten to the sixth power, that is, one million. It is high time our politically correct eminences understood these two non-comparable scales of valuation of the volume and moral meanings of events. It is impossible to accept the ideology of Osamas bin Ladens even remotely comparable to that of say, Pravin Togadia. One is causing a “Une grande Peur” (A great Fear) all over the Western world and the non-Islamic Eastern world. While the other causes nothing because she merely expresses the frustration of common Hindus. An angry Hindu at best draws a derisive laugh among the Islamic world steeped in unimaginable violence. Unimaginable both in methods and scale.

An Excellent Guide

If we want to understand the things in perspective, there is no better guide than Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel. Yes, not even Bernard Lewis or Daniel Pipes has done it with such perfection as the duo (Lewis et al are marred by their West-centric approach, ignoring the role Islam played in Bharat and the difficult Hindu struggle with it for centuries).

Oriana Fallaci has presented the scenario very well on an empirical plane. Addressing those who remained indifferent or harboured illusions about the Talibani destruction of the Buddha statues in Bamiyan she asked,

“Who is next, that the ‘idols’ of Bamiyan have been blown up like twin towers? The other Unfaithful who pray to Vishnu or Shiva, Brahma, Krishna, Annapurna? … Do they hate only the Christian and Buddhists, those voracious sons of Allah, or do they aim to subjugate our whole planet?”

Unfortunately, there are still very few scholars in the West to delve into the issue on a realistic plane.

It is no exaggeration that on philosophical, historical and analytical planes, Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel have presented superior analyses about the Islamic malady. To realise all this, we must first know exactly and thoroughly whatever has been happening all these decades in every corner of the world—from Afghanistan to Sudan, from Palestine to Pakistan, from Malaysia to Iran, from Egypt to Iraq, from Algeria to Senegal, from Syria to Kenya, from Libya to Chad, from Lebanon to Morocco, from Indonesia to Yemen, from Saudi Arabia to Somalia. Only then can one comprehend the hollowness of the artificial balancing of “both Hindu and Muslim” communalism/extremism, which is a routine, mindless practice in our country. In practice, it is nothing but a profound help to the Islamic jihadi politics and terrorism targeting Bharat.

Penetrating Analysis of Islamic Terrorism

The phenomenon of the modern phase of Islamic terrorism arose in the late nineteen sixties. Beginning with September 1970 “Arab terrorism” came to be known in the entire world. No academic or journalist, howsoever politically correct, could then imagine balancing that terrorism with anything else. It was original and Islamic. Balancing it with some US, Israeli or Hindu deeds are a much later invention.

After the beginning of a Euro-Arab dialogue in 1975, and dubious agreements thereafter, petrodollars came pouring into the Western media and academia. The money readily brought subtle and not so subtle messages and conditions. Only then did this kind of artificial balancing began to appear in print. First in France, then in the whole of Europe and American universities. Today from the Harvard University to the London School of Economics to the Jawaharlal Nehru University, from the New York Times to the Economist to the Times of India there are any number of scholars and hacks who compete with each other to explain that anything but Islam is responsible for the acts of Islamic terrorism. That Islam is nothing but basically a religion of peace and brotherhood. And woe betide those who dares contradict this!

That exactly was the refrain towards Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel of our left-secular hacks and professors. Keeping eyes wide shut towards the Islamic nature of so many international problems—violence, bigotry, terrorism, intolerance, etc.—has made the West more vulnerable. It is not the problems attached to gaining insight that made it difficult for the West, but lack of will to say the right thing. The same can be said more assertively about our own country, for we especially prefer the comfortable to the difficult.

Though it has also to do with the traditional Hindu character that remains concerned mostly with swaddharm (one’s own Dharma), and altogether ignored studying and understanding the various religions of the others, the creeds of those aggressors who, driven by permanent hostility and purpose to convert, repeatedly attacked Bharat. This careless attitude to deeply study Islam, Christian missionaries or Communism also played the part for the astonishing Hindu ignorance of Islamic or Communist theory and practices. This in turn, makes the game of the invaders, aggressors, revolutionaries and infiltrators an easy one.

However, as in Europe, here too, the spirit of Munich has been leading the search for insight. The spirit of concessions and compromise, and of cowardice, self-deception by prosperous leaders, scholars and responsible individuals. They all have lost the will to set limits, to be firm. This course has never in the past led to the desired results, including preservation of peace and justice. The experience of Gandhi and the Partition are the most visible examples. But it seems that human emotions are stronger than even the clearest lessons of the past.

Enfeebled Hindu professors, editors and leaders—George Fernandes, the former Defence Minister provided the latest example of Hindu meekness by swallowing and concealing the insults inflicted at the US airports—of Bharat paint sentimental pictures of how violence will generously allow itself to be softened up.

That is not to be.

Primary Sources of Islamic Terror

It is not without reason that of 52 Islamic countries in the world today there is not a single one professing democracy. All are dictatorships and semi-dictatorships of one or another kind, declaredly following Islam. Yes, coercion, intolerance, violence, conquest and propaganda are intrinsic to Islam. From the very beginning, at the place of its birth itself, it could not gain ground except by violence and treachery. So much so that the Arabs, “who had been hitherto upright and chivalrous, became a great scourge and cruel invaders and rulers. Their ethical code suffered a great decline. They began to live on the labour and sweat of others.”

Reading Koran and other authentic primary sources of Islamic literature, one can easily discern that lying and treachery in the cause of Islam has received divine approval. Any hesitation to perjure oneself in that cause is represented as weakness. Consider this. During a synod that the Vatican held in October 1999 to discuss the rapport between Christians and Muslims, an eminent Islamic scholar addressed the stunned audience declaring with placid effrontery, “By means of your democracy we shall invade you, by means of our religion we shall dominate you.” The meaning is clear as daylight.

This typical treachery is on display everywhere in Europe. Islamic migrants force themselves on European people misusing the democratic and humanitarian laws of the respective countries, viciously threatening with “I know my rights” to the local inhabitants. The same “rights” they don’t have, and don’t care to have in their Islamic countries of origin. Some of the perpetrators of 9/11 were on the watchlist of the FBI and CIA. Yet, residing in the USA itself, they could carry out their inhuman mission because the humanitarian laws of the country allowed them the luxury to learn piloting, move around, meet and conspire, and finally to bring down the twin towers of New York.

This is what the Islamic scholar meant.

But as in Bharat so in the West, scholars, leaders and editorial classes have tried to downplay this essential fact. They fail to recognise or don’t want to recognise that a reverse crusade is going on. It is forced on Europe and the USA. Yet their policymakers are trying their best to appease the aggressors. The aggression is an ever-growing reality that the Western leaders senselessly feed and back up. Witness their treatment to Pakistan. Whatever the Bush administration has been looking for in Iraq, to punish Saddam Hussain, were abundantly available in Pakistani territory. Undisguised, under the very US eyes. But instead of taking serious note of it, and appropriate action, they offered Pakistan to be an ally of the NATO! Which attitude is the reason why those crusaders increase in numbers, boss around more and more. They will demand more and more and bully with greater intensity. Till the point of subduing us. Therefore, dealing with them is impossible. Attempting a dialogue, unthinkable. Showing indulgence, suicidal. And he or she who believes the contrary is a fool.

Therefore, the fact must not to be lost sight of, even for a moment, that Islam is more an imperialist, dictatorial, political ideology. It brooks no reform. It severely punishes even members of its own fold, howsoever superior or honourable in knowledge and position for the mere crime of attempting reform.

At this point, it is very important to note that Muslim population and Islam are not the synonymous terms. Just as Marxism-Leninism and Soviet people were not. As criticising Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism-Maoism was not an insult or vilification of the Soviet people or Chinese people, so criticising Islam is not “spreading hate” against Muslims. It is a clever ploy of Islamist scholars, leaders, jihadis as well as Left-secular propagandists in Bharat that they arouse the Muslim masses against any such criticism as though it is directed against them.

Muslims are in most cases as victims of the Imams, Ayatollas, Amirs as the common Russians and Chinese were at the hands of their Marxist masters, the chairman or general secretaries. This ploy has to be fought tooth and nail.

Inasmuch as Islam is a political ideology with a complete social, political, juridical system of its own, it is as liable to criticism and scrutiny as any other political creed. More so as its political ambitions and juridical regulations are never confined to Muslims alone. It has clear rules, regulations and directions applied to non-Muslim masses whether for the moment it is ruling a country or not. Thus the political ideology of Islam, even otherwise, directly affects non-Muslims of the world.

Therefore, not only the Muslim but non-Muslims also have every right to criticise Islam. But the Islamic scholars and ulema using all kinds of pretexts and deceptions, shifting and contradictory—bearing the situation in a given country in mind—deny this right to non-Moslems and Moslems alike. However, as Ram Swarup said so meaningfully, once intellectual freedom is gained for the Moslem masses, rest is only a matter of time. Most Islamic rulers and scholars perceive this very well. Which is why they are hell-bent not to give intellectual freedom to their own brothers in faith, their Moslem subjects. They use every kind of violence, threats, regulations, logics and ploys to deny this.

Why?

The words of Solzhenitsyn quoted in the beginning of this article explain it. It also explains why violence is intrinsic to Islam. Make no mistake. Islamic violence is not a reaction to this or that deed of the West or the Jews or the Hindus. It is because Islam has no intellectual or verbal argument to offer on any point. The erstwhile Soviet scholars used to quote Marxism-Leninism like a spell on all questions. Even if it answered none. Likewise, Islamic scholars quote Koran in every matter, without the slightest regard for or reference to common human reason. That can hardly satisfy inquiring minds, whether non-Moslem or Moslem. That is why Islam regularly employs intimidation and violence to subdue anyone and everyone, anywhere and everywhere, anytime and everytime.

If these essential points are glossed over as have been done in Bharat throughout the 20th century by many respectable leaders and scholars, the Islamic problem can never be understood, let alone solved. Therefore, neither theoretical illusions nor practical difficulties—read fear—should come in way for recognising and fighting this war. As the great living fighter writes,

“In Life and in History there are moments when fear is not permitted. Moments when fear is immoral and uncivilised. And those who out of weakness or stupidity—or the habit of keeping one’s foot in two shoes—avoid the obligations imposed by this war, are not only cowards: they are masochists.”

These are the same values—freedom from ignorance and freedom from fear—that Ram Swarup and Sita Ram Goel tried to instil in us in their gentle, yet firm way. They were intellectual warriors—heroes of our time. – Dharma Dispatch, 24 April 2019

› This essay was first published in the volume, “India’s Only Communalist: In Commemoration of Sita Ram Goel,” edited by Dr. Koenraad Elst

› Shankar Sharan is an Indian author and professor of Political Science at the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) in New Delhi.

A crucial factor here was the choice of language. Ram Swarup himself was quite at home with British culture and thought, being most influenced by British liberalism: Bertrand Russell, George Bernard Shaw, Aldous Huxley, George Orwell. In his case, this didn’t stop him from fighting for freedom from British rule, with active participation in the Quit India Movement. But for less independent minds, gulping down English influence would only end up estranging them from their Hindu roots, as it had done in the case of Jawaharlal Nehru. The vote in the Constituent Assembly’s Language Committee should have been crucial: 50% voted for Sanskrit, 50% for Hindi (which was given victory by the deciding vote of the chairman), and 0% for English. For the generation that had achieved independence, it was completely obvious that decolonisation implied abolishing the coloniser’s language. Yet by 1965, when this abolition was due to become effective, the English-speaking elite had gathered enough power to overrule this solemn commitment. Ever since, the influence of English and of the thought systems conveyed by it has only gone on increasing, and at some levels, India is becoming a part of the Anglosphere—hardly what the freedom fighter envisioned. Today, most Anglophone secularists are nearly as knowledgeable about Hindu culture as first-time foreign tourists who have crammed up the

A crucial factor here was the choice of language. Ram Swarup himself was quite at home with British culture and thought, being most influenced by British liberalism: Bertrand Russell, George Bernard Shaw, Aldous Huxley, George Orwell. In his case, this didn’t stop him from fighting for freedom from British rule, with active participation in the Quit India Movement. But for less independent minds, gulping down English influence would only end up estranging them from their Hindu roots, as it had done in the case of Jawaharlal Nehru. The vote in the Constituent Assembly’s Language Committee should have been crucial: 50% voted for Sanskrit, 50% for Hindi (which was given victory by the deciding vote of the chairman), and 0% for English. For the generation that had achieved independence, it was completely obvious that decolonisation implied abolishing the coloniser’s language. Yet by 1965, when this abolition was due to become effective, the English-speaking elite had gathered enough power to overrule this solemn commitment. Ever since, the influence of English and of the thought systems conveyed by it has only gone on increasing, and at some levels, India is becoming a part of the Anglosphere—hardly what the freedom fighter envisioned. Today, most Anglophone secularists are nearly as knowledgeable about Hindu culture as first-time foreign tourists who have crammed up the