It is time for deconstructionist historians to be deconstructed. Such historians, whose view of the world is purely outward, do not have the insight to appreciate India. … Their historical accounts reflect the attempt of a recent ruling elite to rewrite history in its own image—and to deny legitimacy for any other group, even if it requires denying the very existence of India before they assumed power! – Dr. David Frawley

India today is a strange country in that, uniquely among the nations of the world, it seems to be afraid of its own history.

If we study current historical accounts, particularly by India’s academic Left, the most important fact about the history of India is that there is no real history of India. This is because such scholars are unable to see the existence of any cohesive entity called India before 1947.

India as a real country in their view is attributed mainly to Jawaharlal Nehru and his followers after independence on a region that, though previously under the umbrella of British rule, was otherwise lacking in unity, continuity or perhaps even civilisational depth.

Such historians are happy to negate the history of their own country. Their accounts of India’s history are largely denials of any enduring country, civilisation or culture worthy of the name. Their history of India is one of foreign invasions, temporary or vanished empires, internal social divisions and conflicts, and a disparate and confused cultural diversity. They regard India as a melting pot or conglomeration of widely separated peoples and cultures coming together by the accident of geography that hardly constitutes any united country or national identity.

Unfortunately, such Indian historians, particularly with political alliances with Left historians in UK and US, are introducing their anti-India ideas into Western academia, which still does not understand India’s very different civilisational model.

Such studies forget that national identity is cultural, not simply political. India did not become a British state under British rule or an Islamic state under Muslim rule. The older Indian/Bharatiya culture continued.

These anti-India views are easily countered by a number of historical facts.

The first is that outside people and countries have long recognised a civilisation called India.

After Alexander the Great came to India in the fourth century BCE, the Greek historian Megasthenes wrote a book on the region called Indika, in which he noted an existing tradition in the country of 153 kings going back over 6,400 years. The Greeks overall lauded the civilisation of India.

Buddhist pilgrims in the ancient and medieval period, particularly from China, honoured India and its great culture during their travels. India’s cultural influence spread to Indonesia and Indochina in the East and into Central Asia, extending on a religious level to China and Japan.

The ancient Romans lost much of their wealth in a one-sided trade with India and the Europeans long sought the riches of India. Columbus, of course, found America by chance while looking for a more direct sea route to India.

Second, India, like many countries, has more than one name. The Indian Constitution says the “India that is Bharat”. Bharat is the main ancient name for the region going back to King Bharat, an ancient ruler long before Rama, Krishna or Buddha.

The Bharatas were the main people of the ancient Rig Veda, who ruled from the Sarasvati region. They eventually split into several groups, one of which, the Kurus, became dominant in late ancient times, as the main people of the Mahabharata.

Modern historians can more easily deny history to the name India than to Bharat and so ignore the other name of the country.

Third, India has probably the oldest, largest and most continuous literature of any civilisation. The Vedas with their many thousands of pages dwarf anything from the Middle East, Egypt or Greece of the ancient period.

Geography is an important topic in these texts. The Vedas speak of a land of seven rivers, Sapta Sindhu, extending to the ocean, of which the Sarasvati River was the most important. The Persians in their oldest Zend-Avesta remember the area as Hapta Hindu. Sindhu, Hindu and India are related terms.

The Ramayana, Mahabharata and Puranas outline a sacred geography of India/Bharat from Kailas in the north to Lanka in the south, Assam in the east to beyond the Indus in the west. Buddhist and Jain texts do the same, showing a common culture and geography.

Around this sacred geography, Indians built numerous temples and recognised numerous sacred sites, revealing this vast region and its cultural unity.

Along with these sacred sites are numerous festivals and pilgrimages. We see this in modern India, which has the largest tradition of pilgrimage in the world, notably the massive Kumbha Melas that bring in tens of millions of pilgrims. Pilgrims throughout India visit these sites, with South Indians commonly travelling as far as the Himalayan temples of the north. Festivals like Diwali are elaborately celebrated throughout the country.

Ancient Indian literature contains a calendar system still widely followed, the Panchanga. Indian calendars extend from historical time of thousands of years to cosmic time of billions of years.

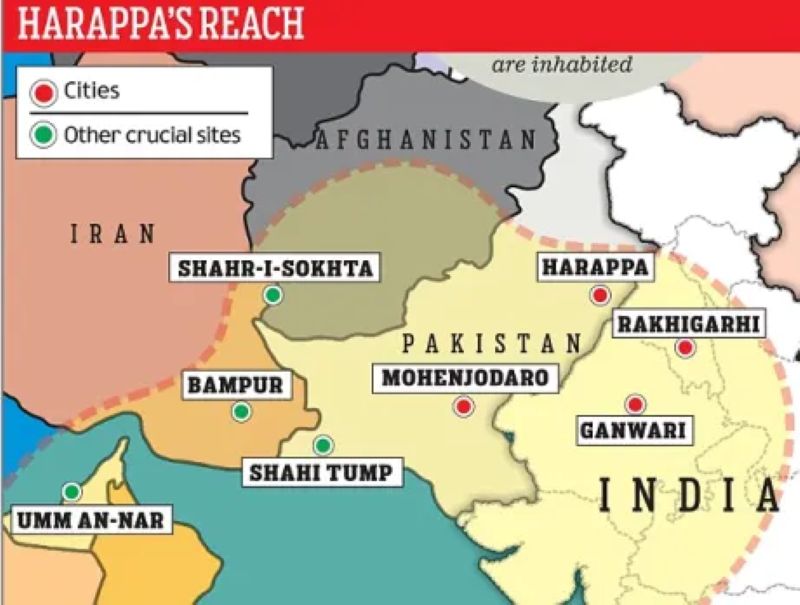

Fourth, extensive new evidence of archaeology upholds the cultural continuity of the region. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) claims that in the Haryana/Kurukshetra/Sarasvati river area there is evidence of a continual development of agriculture and civilisation from 8000 BCE, extending through the Harappan urban era. This area hosts Rakhigarhi, the largest Harappan site, more extensive than Mohenjodaro or Harappa.

The Harappan Civilization—also called the Indus Valley or Saraswati Civilisation—is the largest and most uniform urban civilisation of the ancient world in the third millennium BCE. It ended with the drying up of the Sarasvati River around 1900 BCE, which the Geological Survey of India (GSI) has verified. The Vedas refer to the different stages of the Sarasvati river from an ocean-going stream to drying up in the desert, showing they resided on the river long before its termination.

Consistent with their negative line of thought, Leftist historians ignore this information or accuse archaeologists of political bias in their findings.

Lastly, but equally important, the independence movement drew inspiration from the older history of India/Bharat, with such revered figures as Swami Vivekananda, Lokmanya Tilak and Sri Aurobindo seeking to revive the ancient culture. Even Mahatma Gandhi’s mantra was Ram and his idea of India was Ram Rajya.

Not surprisingly, most of these independence leaders have been ignored by the same group of historians, who have made Nehru tower over them, with some afforded diminished roles and others forgotten altogether.

The Congress party, the main support for such historians, has since named every major institution or initiative in India possible after the three members of the Nehru family who became prime ministers. They have little regard for other Congress prime ministers like P.V. Narasimha Rao, whom they have also almost erased from history.

Yet at the same time today, India’s great culture and civilisation through Yoga, Vedanta, Buddhism, Sanskrit, Indian music and dance is once more influencing the entire world—expanding in spite of this historical denigration.

It is time for these deconstructionist historians to be deconstructed. Such historians, whose view of the world is purely outward, do not have the insight to appreciate India, because it is not a mere political formation but a vast spiritual culture.

Their historical accounts reflect the attempt of a recent ruling elite to rewrite history in its own image—and to deny legitimacy for any other group, even if it requires denying the very existence of India before they assumed power! – Vedanet, 30 June 2016

›This article originally appeared in Swarajya Magazine.

› Dr David Frawley (Pandit Vamadeva Shastri) is a Vedacharya and includes in his unusual wide scope of studies Ayurveda, Yoga, Vedic astrology, and Indian History.