The late Sita Ram Goel, a prominent historian, author, and publisher, had Left leanings during the 1940s, but later became an outspoken anti-Communist. He also wrote extensively on the damage to Bharatiya culture and heritage wrought by Nehruism. The article below is an extract from Goel’s book, How I Became a Hindu, first published by Voice of India in 1982.

Today, I view Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru as a bloated brown sahib, and Nehruism as the combined embodiment of all the imperialist ideologies—Islam, Christianity, White Man’s Burden, and Communism—that have flooded this country in the wake of foreign invasions. And I do not have the least doubt in my mind that if India is to live, Nehruism must die. Of course, it is already dying under the weight of its sins against the Indian people, their country, their society, their economy, their environment, and their culture. What I plead is that a conscious rejection of Nehruism in all its forms will hasten its demise, and save us from the mischief which it is bound to create further if it is allowed to linger.

I have reached this conclusion after a study of Pandit Nehru’s writings, speeches and policies ever since he started looming large on the Indian political scene. But lest my judgement sounds arbitrary, I am making clear the premises from which I proceed. These premises themselves have been worked out by me through prolonged reflection on the society and culture to which I belong.

I have already described how I returned to an abiding faith in Sanatana Dharma under the guidance of Ram Swarup. The next proposition which became increasingly clear to me in discussions with him, was that Hindu society which has been the vehicle of Sanatana Dharma is a great society and deserves all honour and devotion from its sons and daughters. Finally, Bharatavarsha became a holy land for me because it has been and remains the homeland of Hindu society.

There are Hindus who start the other way round, that is, with Bharatavarsha being a holy land (punyabhumi) simply because it happens to be their fatherland (pitribhumi) as well as the field of their activity (karmabhumi). They honour Hindu society because their forefathers belonged to it, and fought the foreign invaders as Hindus. Small wonder that their notion of nationalism is purely territorial, and their notion of Hindu society no more than tribal. For me, however, the starting point is Sanatana Dharma. Without Sanatana Dharma, Bharatavarsha for me is just another piece of land, and Hindu society just another assembly of human beings. So my commitment is to Sanatana Dharma, Hindu society, and Bharatavarsha—in that order.

In this perspective, my first premise is that Sanatana Dharma, which is known as Hinduism at present, is not only a religion but also a whole civilisation which has flourished in this country for ages untold, and which is struggling to come into its own again after a prolonged encounter with several sorts of predatory imperialism. On the other hand, I do not regard Islam and Christianity as religions at all. They are, for me, ideologies of imperialism. I see no place for them in India, now that India has defeated and dispersed Islamic and Christian regimes.

I have no use for a secularism which treats Hinduism as just another religion, and puts it on par with Islam and Christianity. For me, this concept of secularism is a gross perversion of the concept which arose in the modern West as a revolt against Christianity and which should mean, in the Indian context, a revolt against Islam as well. The other concept of secularism, namely, sarva dharma samabhava, was formulated by Mahatma Gandhi in order to cure Islam and Christianity of their aggressive self-righteousness, and stop them from effecting conversions from the Hindu fold. This second concept was abandoned when the Constitution of India conceded to Islam and Christianity the right to convert as a fundamental right. Those who invoke this concept in order to browbeat the Hindus are either ignorant of the Mahatma’s intention, or are deliberately distorting his message.

My second premise is that Hindus in their ancestral homeland are not a mere community. For me, the Hindus constitute the nation, and are the only people who are interested in the unity, integrity, peace and prosperity of this country. On the other hand, I do not regard the Muslims and the Christians as separate communities. For me, they are our own people who have been alienated by Islamic and Christian imperialism from their ancestral society and culture, and who are being used by imperialist forces abroad as their colonies for creating mischief and strife in the Hindu homeland. I therefore, do not subscribe to the thesis that Indian nationalism is something apart from and above Hindu nationalism.

For me, Hindu nationalism is the same as Indian nationalism. I have no use for the slogans of “composite culture”, “composite nationalism” and “composite state”. And I have not the slightest doubt in my mind that all those who mouth these slogans as well as the slogan of “Hindu communalism”, are wittingly or unwittingly being traitors to the cause of Indian nationalism, no matter what ideological attires they put on and what positions they occupy in the present set-up.

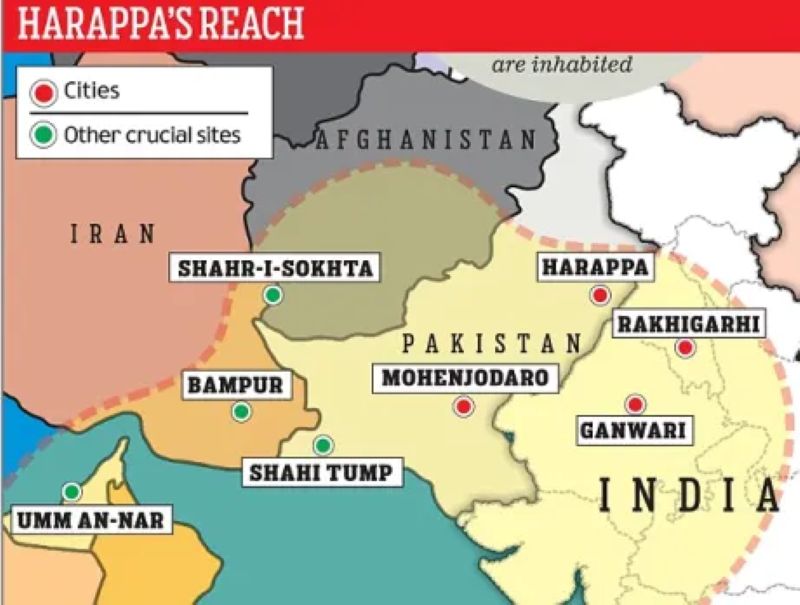

My third premise is that Bharatavarsha has been and remains the Hindu homeland par excellence. I repudiate the description of Bharatavarsha as the Indian or Indo-Pak subcontinent. I refuse to concede that Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh have ceased to be integral parts of the Hindu homeland simply because they have passed under the heel of Islamic imperialism. Hindus have never laid claim to any land outside the natural and well-defined borders of their ancient homeland, either by right of conquest or by invoking a promise made in some scripture. I, therefore, see no reason why Hindus should surrender their claim to what they have legitimately inherited from their forefathers but what has been taken away from them by means of armed force. Moreover, unless the Hindus liberate those parts of their homeland from the stranglehold of Islam, they will continue to face the threat of aggression against the part that remains in their possession at present. These so-called Islamic countries have been used in the past, and are being used at present as launching pads for the conquest of India that has survived.

My fourth premise is that the history of Bharatavarsha is the history of Hindu society and culture. It is the history of how the Hindus created a civilisation which remained the dominant civilisation of the world for several millennia, how they became complacent due to excess of power and prosperity and neglected the defences of their homeland, how they threw back or absorbed in the vast complex of their society and culture a series of early invaders, and how they fought the onslaughts of Islamic, Christian, and British imperialism for several centuries and survived.

I do not recognise the Muslim rule in medieval India as an indigenous dispensation. For me, it was as much of a foreign rule as the latter-day British rule. The history of foreign invaders forms no part of the history of India, and remains a part of the history of those countries from which the invaders came, or of those cults to which they subscribed. And I do not accept the theory of an Aryan invasion of India in the second millennium BC. This theory was originally proposed by scholars as a tentative hypothesis for explaining the fact that the language spoken by the Indians, the Iranians and the Europeans belong to the same family. And a tentative hypothesis it has remained till today so far as the world of scholarship is concerned. It is only the anti-national and separatist forces in India which are presenting this hypothesis as a proven fact in order to browbeat the Hindus, and fortify their divisive designs. I have studied the subject in some depth, and find that the linguistic fact can be explained far more satisfactorily if the direction of Aryan migration is reversed.

These are my principal premises for passing judgement on Pandit Nehru and Nehruism. Many minor premises can be deduced from them for a detailed evaluation of India’s spiritual traditions, society, culture, history, and contemporary politics. It may be remembered that Pandit Nehru was by no means a unique character. Nor is Nehruism a unique phenomenon for that matter. Such weak-minded persons and such subservient thought processes have been seen in all societies that have suffered the misfortune of being conquered and subjected to alien rule for some time. There are always people in all societies who confuse superiority of armed might with superiority of culture, who start despising themselves as belonging to an inferior breed and end by taking to the ways of the conqueror in order to regain self-confidence, who begin finding faults with everything they have inherited from their forefathers, and who finally join hands with every force and factor which is out to subvert their ancestral society. Viewed in this perspective, Pandit Nehru was no more than a self-alienated Hindu, and Nehruism is not much more than Hindu-baiting born out of and sustained by a deep-seated sense of inferiority vis-a-vis Islam, Christianity, and the modern West.

Muslim rule in medieval India had produced a whole class of such self-alienated Hindus. They had interpreted the superiority of Muslim arms as symbolic of the superiority of Muslim culture. Over a period of time, they had come to think and behave like the conquerors and to look down upon their own people. They were most happy when employed in some Muslim establishment so that they might pass as members of the ruling elite. The only thing that could be said in their favour was that, for one reason or the other, they did not convert to Islam and merge themselves completely in Muslim society. But for the same reason, they had become Trojan horses of Islamic imperialism, and worked for pulling down the cultural defences of their own people. The same class walked over to the British side when British arms became triumphant. They retained most of those anti-Hindu prejudices which they had borrowed from their Muslim masters, and cultivated some more which were contributed by the British establishment and the Christian missions. That is how British rule became a divine dispensation for them. The most typical product of this double process was Raja Ram Mohun Roy.

Fortunately for Hindu society, however, the self-alienated Hindu had not become a dominant factor during the Muslim rule. His class was confined to the urban centres where alone Muslim influence was present in a significant measure. Second, the capacity of Islam for manipulating human minds by means of ideological warfare was less than poor. It worked mostly by means of brute force, and aroused strong resistance. Finally, throughout the period of Muslim rule, the education of Hindu children had remained in Hindu hands by and large. So the self-alienated Hindu existed and functioned only on the margins of Hindu society, and seldom in the mainstream.

All this changed with the coming of the British conquerors and the Christian missionaries. Their influence was not confined to the urban centres because their outposts had spread to the countryside as well. Second, they were equipped with a stock of ideas and the means for communicating them which were far more competent as compared to the corresponding equipment of Islam. And what made the big difference in the long run was that the education of Hindu children was taken over by the imperialist and the missionary establishments. As a cumulative result, the crop of self-alienated Hindus multiplied fast and several fold.

Add to that the blitzkrieg against authentic Hindus and in favour of the self-alienated Hindus mounted by the Communist apparatus built up by Soviet imperialism. It is no less than a wonder in human history that Hindu society and culture not only survived the storm, but also produced a counter-attack under Maharshi Dayananda, Swami Vivekanand, Sri Aurobindo and Mahatma Gandhi such as earned for them the esteem of the world at large. Even so, the self-alienated Hindus continued to multiply and flourish in a cultural milieu mostly dominated by the modern West.

And they came to the top in the post-Independence period when no stalwart of the Hindu resurgence remained on the scene. The power and prestige which Pandit Nehru acquired within a few years after the death of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel had nothing to do with his own merits, either as a person, or as a political leader, or as a thinker. They were the outcome of a long historical process which had brought to the fore a whole class of self-alienated Hindus. Pandit Nehru would have never come to the top if this class had not been there. And this class would not have become dominant or remained so, had it not been sustained by establishments in the West, particularly that in the Soviet Union.

It is not an accident that the Nehruvian regime has behaved like the British Raj in most respects. The Nehruvians have looked at India not as a Hindu country but as a multi-racial, multi-religious and multi-cultural cockpit. They have tried their best, like the British, to suppress the mainstream society and culture with the help of “minorities”, that is, the colonies crystallised by imperialism. They have also tried to fragment Hindu society, and create more “minorities” in the process. In fact, it has been their whole-time occupation to eliminate every expression of Hindu culture, to subvert every symbol of Hindu pride, and persecute every Hindu organisation, in the name of protecting the “minorities”, Hindus have been presented as monsters who will commit cultural genocide if allowed to come to power.

The partition of the country was brought about by Islamic imperialism. But the Nehruvians blamed it shamelessly on what they stigmatised as Hindu communalism. A war on the newly born republic of India was waged by the Communists in the interests of Soviet imperialism. But the Nehruvians were busy apologising for these traitors, and running hammer and tongs after the RSS. There are many more parallels between the British Raj on the one hand and the Nehruvian regime on the other. I am not going into details because I am sure that the parallels will become obvious to anyone who applies his mind to the subject. The Nehruvian formula is that Hindus should stand accused in every situation, no matter who is the real culprit. – How I became a Hindu, 1982