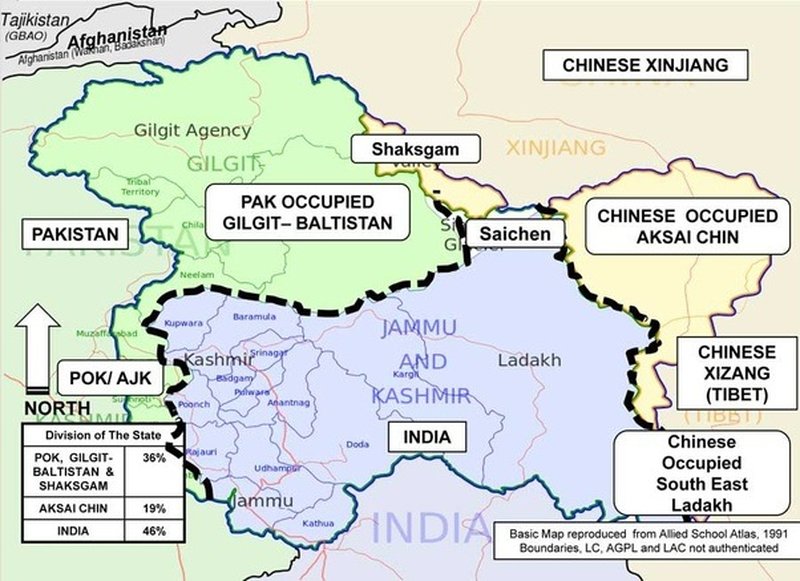

Despite Raja Hari Singh having signed the Instrument of Accession and joined India, Maj. William Brown of the Gilgit Scouts refused to acknowledge the orders of the Maharaja, and on November 1, 1947, he handed over the entire area of Gilgit-Baltistan to Pakistan. – Claude Arpi

On May 4, during an interactive session at the Arctic Circle India Forum 2025, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar spoke of broader geopolitical upheavals affecting the world, in particular Europe, which “must display some sensitivity and mutuality of interest for deeper ties with India”.

Answering a question on India’s expectations from Europe, Jaishankar said, “When we look out at the world, we look for partners; we do not look for preachers, particularly preachers who do not practice at home and preach abroad.”

This sharp answer came after the EU’s top diplomat, Kaja Kallas, urged both India and Pakistan to exercise restraint.

Kaja Kallas, the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, formerly a Prime Minister of Estonia, was obviously ill-informed about the situation in Kashmir (and along the India-Pakistan border).

The attitude of certain Western countries (as well as the UN General Secretary) represents a great danger for India today; it has been so in the past.

The Kashmir Issue

A few years ago, while researching in the Nehru papers, I came across a “Top Secret” note written in the early 1950s by Sir Girja Shankar Bajpai, then secretary-general of the Ministry of External Affairs and Commonwealth Affairs; it was entitled “Background to the Kashmir Issue: Facts of the Case”; it made fascinating reading.

It started with a historical dateline: “Invasion of the state by tribesmen and Pakistan nationals through or from Pakistan territory on October 20, 1947; the ruler’s offer of accession of the state to India supported by the National Conference, a predominantly Muslim though non-communal political organisation, on October 26, 1947; acceptance of the accession by the British Governor-General of India on October 27, 1947; under this accession, the state became an integral part of India.”

Unfortunately, in a separate note, Lord Mountbatten, the Governor General of India, mentioned a plebiscite which would “take place at a future date when law and order had been restored and the soil of the state cleared of the invader”, then “the people of the state were given the right to decide whether they should remain in India or not.”

It was an unnecessary addition, but Mountbatten wanted to show British (so-called) legendary fairness.

Anyway, the conditions were clear and in two parts: first, the Pakistani troops or irregulars should withdraw from the Indian territory that they occupied, and later a plebiscite could be envisaged.

Bajpai’s note also observed: “Pakistan, not content with assisting the invader, has itself become an invader, and its army is still occupying a large part of the soil of Kashmir, thus committing a continuing breach of international law.”

The Gift of Gilgit

Worse was to come; Maj. William Brown, a British officer, illegally offered Gilgit to Pakistan. The British paramountcy had lapsed on August 1, 1947, and Gilgit had reverted to the Maharaja’s control. Lt. Col. Roger Bacon, the British political agent, handed his charge to Brig. Ghansara Singh, the new governor appointed by Maharaja Hari Singh, while Maj. Brown remained in charge of the Gilgit Scouts.

Despite Hari Singh having signed the Instrument of Accession and joined India, Maj. Brown refused to acknowledge the orders of the Maharaja under the pretext that some leaders of the Frontier Districts Province (Gilgit-Baltistan) wanted to join Pakistan.

On November 1, 1947, he handed over the entire area to Pakistan, in all probability ordered by the British generals.

An interesting announcement appeared in the 1948 London Gazette mentioning that the King “has been graciously pleased … to give orders for … appointments to the Most Exalted Order of the British Empire.…” The list included “Brown, Major (acting) William Alexander, Special List (ex-Indian Army)”. Brown was knighted for having served the Empire.

At the time, the entire hierarchy of the Indian and Pakistan Army were still British. In Pakistan, Sir Frank Messervy was commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Army in 1947-48, and Sir Douglas Gracey served in 1948-51; while in India, the commander-in-chief was Sir Robert Lockhart (1947-48) and later Sir Roy Bucher (1948), and let us not forget that Sir Claude Auchinleck (later elevated to Field Marshal) served as the supreme commander (India and Pakistan) from August to November 1947.

Who can believe that all these senior generals were kept in the dark by a junior officer like Maj. Brown?

The Western influence or manipulation continued in the following years and decades; the Americans soon entered the scene too.

India and the Western Powers

After China invaded northern India in 1962, Delhi decided to ask for the help of the Western nations, particularly the United States. The latter was only too happy to offer it and thus gain leverage over India, which until that time had been “neutral and non-aligned”.

Seeing northern India invaded by Chinese troops, it seemed logical that the United States would come to India’s aid, but it turned out differently.

Soon after the ceasefire declared by the Chinese on November 22, 1962, and instead of helping India, Great Britain and the United States decided that the time had come to resolve the Kashmir dispute between their Pakistani ally and India, now begging for help.

Two days after the ceasefire, Averell Harriman, the US Under Secretary of State, and Duncan Sandys, the British Commonwealth Secretary, visited the two capitals of the subcontinent to persuade the “warring brothers” that it was time to bury the hatchet and find a solution to the fifteen-year-old Kashmir question. Harriman and Sandys signed a joint communiqué and asked the two countries to resume negotiations.

India’s invasion by China was forgotten.

Delhi, in a position of extreme weakness, had doubts about the possibility of obtaining positive results from negotiations conducted under such circumstances, but Nehru did not refuse the “offer”.

On December 22, 1962, he wrote to the provincial chief ministers: “I have to speak to you briefly on the Indo-Pakistan question, and particularly on Kashmir. In four days, Sardar Swaran Singh [the Minister of External Affairs] will lead a delegation to Pakistan to discuss these problems. We realise that this is not the right time to have a conference like this, as the Pakistani press has vitiated the atmosphere with insults and attacks directed against India. Nevertheless, we have agreed to go and will do our best to arrive at a reasonable solution.”

The two delegations ultimately held a series of six meetings; nothing came of them. The first negotiations took place in Rawalpindi; Swaran Singh and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan’s foreign minister, limited themselves to a historical presentation of the problem and the reiteration of their respective points of view. During the talks, India reaffirmed that it wanted to explore all possibilities to resolve the issue, as it wanted to live in peace with Pakistan, which insisted that the UN resolutions of August 1948 and January 1949 must be implemented as soon as possible (without them vacating the occupied part of Hari Singh’s kingdom).

The negotiations got off on a bad start: just before they began, the Pakistani government announced that it had reached an agreement in principle with China on its border issue. Just a month after the end of the Sino-Indian War, Pakistan was prepared to give China a piece of territory that India considered its own. What a slap in the face for India! Were the Western powers aware of the secret negotiations between Pakistan and China? Probably.

It is indeed surprising that Pakistan, an ally of the United States and the Western world, chose this moment to make this announcement. It was proof that Pakistan expected nothing from the talks with Delhi.

Negotiations on Kashmir continued between January 16 and 19, 1963, in Delhi and February 8 and 11 in Karachi, of course without any tangible results. Pakistan wanted a plebiscite, but India insisted on the prior demilitarisation of the regions occupied by Pakistan.

Talks took place in Calcutta between March 12 and 14. India proposed some readjustments of the Line of Control, but these were rejected by Pakistan.

During the fifth round of talks held in Karachi between April 22 and 25, India protested that Pakistan had ceded part of Kashmiri territory to China; there was no longer any chance of finding a negotiated solution to the Kashmir issue.

During the sixth and final round of talks, India clarified that it had no intention of replacing a democratically elected government with an international organisation that it believed had no knowledge of local issues. India therefore rejected the proposals.

Retrospectively, 63 years later, it is not surprising that in an interview with Sky News, when the interviewer Yalda Hakim questioned him about Pakistan’s long history of backing, supporting and training terrorist organisations, Pakistan Defence Minister Khawaja Asif admitted, “Well, we have been doing this dirty work for the United States for about three decades, you know, and the West, including Britain.”

India should indeed beware of some Western powers. – Firstpost, 10 May 2025

› Claude Arpi is Distinguished Fellow, Centre of Excellence for Himalayan Studies, Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence, Delhi. He is the director of the Pavilion of Tibetan Culture at Auroville.