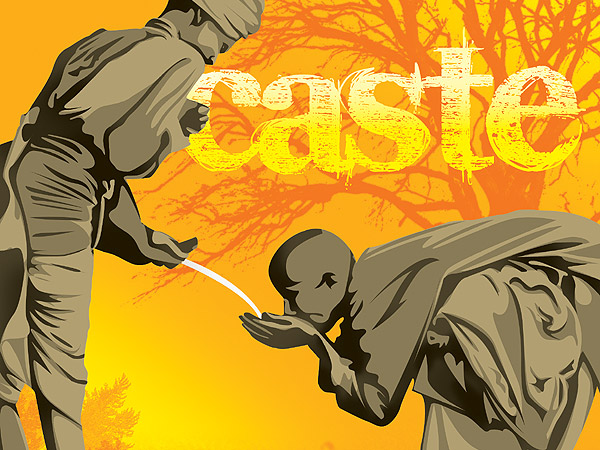

India’s tragedy is that somewhere in history, caste and dharma were kneaded together like salt in dough. What began as a division of labour merged with notions of virtue and sin. Acting within one’s caste became dharma; going outside it became sin. – Acharya Prashant

Every few years, incidents remind us that caste persists in different avatars. Our Constitution guarantees equality, yet divisions control how we live, marry, vote, and worship. Knowingly or unknowingly, we judge people by birth. Caste survives despite legal systems, educational programs, and metropolitan anonymity.

We wrongly believe social reform alone can fix what is mostly psychological. Caste is not a census number; it is a paradigm of evaluation. People constitute systems; as long as people don’t inwardly change, systemic change won’t help much.

Caste and the Constitution

The Constitution guarantees liberty, equality, and fraternity. Yet caste persists because exclusivity, superiority, and material benefits are irresistible. Caste has become ingrained in habit, rooted in livelihood, kinship, and identity. Our constitutional principles are like rangoli patterns on the ground; they cannot change the soil underneath.

That soil pervades everyday life. Many trades favour one community over another. Marriage remains mostly endogamous, with nine of ten unions within caste. Lineage maps out towns and villages. And when voting time comes, we rarely cast our vote; we vote our caste.

When Caste Masquerades as Dharma

The persistence of caste cannot be explained by sociology alone. Laws may impact behaviour and reforms may change customs, but neither explains nor eradicates how caste has been sanctified in dharma’s name.

For humans, consciousness is paramount. An insult to self-worth hurts far more than bodily injury. More than our flesh, we protect our ‘feeling’ of being right: our dharma. Dharma is the inner compass for right seeing and living, man’s most sacred possession, guiding all people.

India’s tragedy is that somewhere in history, caste and dharma were kneaded together like salt in dough. What began as a division of labour merged with notions of virtue and sin. Acting within one’s caste became dharma; going outside it became sin.

If caste were only a social structure, reformers would have erased it. If merely legal, the Constitution would suffice. But caste is sustained in religious belief. It persists because it hides behind Dharma’s name.

As long as this false dharma based on birth endures, caste will endure. What is worshipped will not be questioned, and what is not questioned will not change.

The History of Caste: The Distortion of Dharma

To understand why caste became inseparable from Indian life, let’s start from the beginning. The Purusha Sukta in the Rigveda speaks of an all-encompassing Being from whom everything comes. The hymn is metaphorical: the Brahmin came from His mouth, the Kshatriya from His arms, the Vaishya from His thighs, the Shudra from His feet. The symbolism points at how every form of work emerges from the same living whole, without any mention of hierarchy.

The Rigveda differentiates between Arya and Dasa, indicating early social stratification. There is still a dispute about whether varna was originally fluid or hierarchical. The goal is not to prove a perfect history, but to understand that any tradition has both liberating and limiting parts. It is our ethics that decide the thread we will follow next.

The Upanishads are the best argument against caste because they don’t just reject birth-based differences; they also reject body identification. The Vajrasuchika Upanishad, for example, directly emphasises that caste is unreal. The Bhagavad Gita said that varna comes from guna (individual physical tendencies) and karma (individual choices), not birth.

Such scriptures were being composed and had sublime philosophy emphasizing egalitarianism. However, there was a critical lapse: the scriptures were limited to a few meditative thinkers who mostly remained aloof and out of touch with mainstream society. The authors of the scriptures presented their insights in books, but did not get into grounded social activism to turn the spiritual insights into social reality. So, concurrently with the heights of meditative revelations, the social order continued to have strong currents of discrimination. By about 400 BC, the Dharmasutras emerged to become practical social guides. ‘Dharma’ began to mean social order. Spiritual symbolism became social distortion, and these new ‘scriptures’ started to show inequality based on caste. Over time, these grew into Dharmashastras, remembered as law codes such as the Manusmriti. Here lay the tipping point. The Purusha Sukta was reread with harmful additions: claims of Brahmin superiority, prohibitions on hearing the Vedas, and punishments for non-compliance. The spiritual metaphor became a manual of social control.

Later, the Puranas reinforced these distortions. With the Puranas’ dualistic approach came theism, and the social order was declared divinely ordained. Now, rebelling against caste meant rebelling against God, who made the caste system. Story after story contained subtle caste validation. Divine avatars were consistently born into upper castes, while those who challenged varna faced curses or calamity. The logic was circular but effective: if the gods themselves observed caste, it must be cosmic law. In dualistic theology, God becomes the author of worldly hierarchy. What Advaitic philosophy had rejected, mythology now sanctified.

Advaita Vedanta maintained a steadfast intellectual stance: since all distinctions are illusory, how can caste be authentic? But as caste became the dominant social system, even Advaita found itself compromised between transcendental truth (paramarthik) and practical social order (vyavaharik). The peak of truth was accepted as the highest, but was made distant from the ground of lived reality.

Caste’s story, however, is not one of unbroken supremacy. The Buddha did not accept the authority of the Brahmins. Bhakti poets Saints Kabir, Ravidas, and Chokhamela ridiculed caste. Basava’s Veerashaivism and Guru Nanak’s teachings went against the idea of a hierarchy. However, even as Bhakti emphasized that all individuals are equal in the eyes of God, it did not quite revolt against the unequal social hierarchy. A strange co-existence of unequal social order with equality before God was not just accepted, but institutionalized in Bhakti mythology, social order and rituals.

The reform movements show that resistance to caste often does arise within the religious system. But the idea of equality is often reabsorbed by the strong current of social inertia. What started as a misinterpretation of scripture became a social law, then a habit, and finally institutionalized heredity. The lesson is serious: to fight caste, you need both spiritual clarity and institutional change.

The Economics of Discrimination

Endogamy, or marrying within one’s own group, is at the heart of caste. It keeps bloodlines and a sense of belonging, while creating psychological walls. When marriage becomes restricted, so does social intimacy—families stop sharing meals, homes, and lives with those outside their group. Communities that marry within closed circles risk losing genetic diversity and cultural exchange. The biological costs are real, but the cultural impoverishment runs deeper: when people cannot marry across lines, they struggle to see each other as equals.

Yet caste continues not just as a belief but also as a source of profit. The priest’s ritual authority gave him power over knowledge, while the landlord’s caste position made his hold on land and labour even stronger. Endogamy preserved not just bloodlines but property. By ensuring daughters married within the caste, families kept wealth and land concentrated, turning social boundaries into economic moats that protected privilege across generations.

The Path Forward: Returning from Smriti to Shruti

The solution cannot principally come from courts; it must arise from understanding dharma itself. Sanatan Dharma was never meant to be a set of strict rules and inherited beliefs. It was the dharma of Shruti, the direct revelation of Truth. The emphasis was on clarity of consciousness, not on divine commandments. Social order was to be a spontaneous and fluid outcome of individual realization. Over time, however, we began living by Smriti, frozen law, and social convention.

As long as Smriti remained faithful to Shruti, it guided society; when it diverged, it enslaved society. Much of what we call “Hindu practice” belongs to this later distortion, drawn more from the Manusmriti and Puranas than the Upanishads. We talk about Vedic heritage, yet we live by hierarchies that came after the Vedic period.

This appeal to return to Shruti has a crucial objection: what if the texts themselves are complicit? What if hierarchy is inherent rather than incidental?

We need to consider this criticism. If the Upanishads were enough, why did Vedantic philosophy persist alongside millennia of discrimination? Sublime texts alone do not ensure accurate interpretation. The conclusion is stark: for each truthful scripture, we also need an equally truthful interpreter. The interpretation, practically, is as important as the scripture itself. And this interpretation must be made socially widespread, though that task will face resistance from those whose power depends on distortion. So, we need culture and powerful institutions to ensure and defend scriptural wisdom’s rigorous interpretation and dissemination.

And a note of caution to the sage-philosopher: your job doesn’t stop at meditation, revelation and publication. You need to get into the society and ensure that the light seen by you becomes the living light of the common man. The philosopher, the meditator, the thinker can’t afford to hide in his cave, he will have to be, firstly a rebellious social activist, and secondly, a meticulous institution-builder. This will mean getting into the din of public life and sacrificing the serenity he so lovingly cherishes, but that’s the sacrifice life and history demand of him. If he refuses, the consequences of his self-absorption will be socially devastating.

Democratization of Interpretation

We must ask who has the authority to interpret Shruti. In the past, only Brahmins, especially priests, had that right. But we cannot have the same gatekeepers who let the truth get distorted in charge of bringing it back.

It is important to make interpretation more democratic. Shruti should be accessible not as a privilege but as a birthright of consciousness. This means having translations of the Upanishads in the vernacular language, open discourse, and the recognition that spiritual realisation, not lineage, is what qualifies someone to understand the Upanishads.

When religion diverges from philosophy, it transforms into a blind and violent force, serving as a tool of fear rather than liberation. The Upanishadic view starts where hierarchy stops. It sees the sacred not in birth but in realisation.

In Vedanta’s light, every division dissolves. The way forward is cleansing religion, valuing truth over tradition, realisation over recollection. No interpretation of any scripture is valid if it violates the principles inherent in the Mahavakyas “Aham Brahmasmi” and “Tat Tvam Asi”.

The Path in Practice

It begins with modern, scientific education of the ego-self in school and college curricula. Students must be exposed to the process of biological and social conditioning, the matter of false identities, and the question “Who am I?”.

Cultural change valuing the Upanishads over the Manusmriti must be promoted, as well as rigorous interpretation of Smriti texts true to the spirit of Vedanta. Religious institutions must open doors regardless of birth, and spiritual leaders should publicly reject caste-based privilege.

Legal and economic measures too remain vital: affirmative action, anti-discrimination enforcement, and equalisation of opportunity. The soil is renewed not by one hand alone but by many: the teacher, the reformer, the legislator, and the rebel. – The Pioneer, 8 November 2025

› Acharya Prashant is a spiritual teacher, philosoper, poet and author of wisdom literature.