The over-arching need to find common ground with Abrahamic faiths … has at the very heart of it the belief that Hinduism is somehow inferior to the supremacist, monopolist and violent monotheistic religions. – Yogendra Singh Thakur

Some time ago, the former Lok Sabha Speaker and Union Minister Shivraj Patil claimed that Hinduism has a concept of “jihad” similar to the one in Islam. Patil, highlighting that there is a lot of discussion on jihad in Islam, said that “the concept comes to the fore when despite having the right intentions and doing the right thing, nobody understands or reciprocates, then it is said one can use force.”

“It is not just in Quran, but in Mahabharata also, the part in Gita, Shri Krishna also talks of jihad to Arjun and this thing is not just in Quran or Gita but also in Christianity,” he said adding further fuel to the fire.

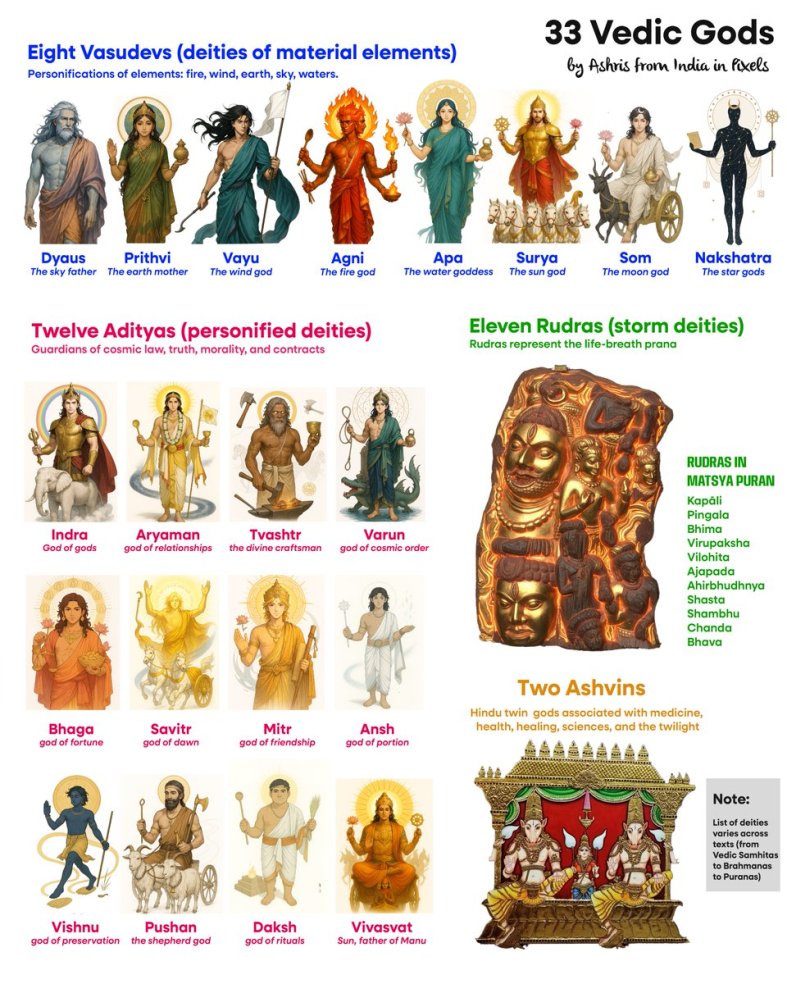

Faced with the natural and correct backlash on the statement, Patil attempted to dress the wound with a clarification. But the dressing was evidently soaked in salt as the clarification only worsened the situation. Patil went on to say that just as Islam and Christianity, Hinduism too does not endorse many gods but only one. Such a god has “no colour, no shape and no form,” he said. Basically, the former Union Minister was pushing the monotheistic belief—the existence of one sole formless god—which is the very foundation of Abrahamic faiths. This is the same belief which has been at odds with polytheistic Hinduism for centuries, leading to the many wars initiated and instigated by Muslims and Christians, the ethnic genocides that these two religions have carried out worldwide and in India, and even caused the Partition of the country.

Some days ago, another political leader from the state of Karnataka, made an ill-intentioned remark on Hinduism, calling the word Hindu, “dirty”. The leader went on to remark that we should rise above the boundaries of religion and that “it is not appropriate to glorify anything related to Hinduism.” One wonders why it is always that Hindus and Hinduism are targeted whenever there is a call to rise above religion and religious identity, and that these calls are usually followed or accompanied by abusing only Hinduism and Hindus.

This idea about rising above religion or a notion that religion, when it comes to Hinduism, is something to be insecure about is not limited to the remarks of ignorant and mischievous political leaders alone. The Supreme Court has very famously stated that Hinduism is not a religion but a way of life. What this statement evidently implies is that Hinduism is a cultural belief system with rituals, festivals, and beliefs about life and death, and it does not contain any larger social regulation system, any system of doctrines or practices related to spirituality or worship, that it does not have anything to do with the sacred, holy, absolute, divine, and of special reverence, or that Hindus do not have ant political aspirations as a community. Hence in a scenario when such a system is built or such aspirations are formed, it becomes, by definition, “un-Hindu”: Hindus are merely amoebic, shape-shifting human beings in this conception of the Supreme Court of India.

This is what senior Congress leader Salman Khurshid asserted, when he claimed that Hindutva, which advocates for certain political interests of Hindu society, is similar to Boko Haram and ISIS terrorist outfits. But despite such cruel, false, and provocative comparisons drawn on the basis of “Hinduism is a way of life” notion, many do like to continue advocating it, including our current Prime Minister himself.

It is this notion alone which is at the heart of an advocacy that Hindus are not a people following one religion but a people identifying with a certain culture, irrespective of religious affiliations—the kind of advocacy which the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) chief, Dr Mohan Bhagwat, does quite often. Dr Bhagwat often expresses that they “have been telling since 1925 (when the RSS was founded) that everyone living in India is a Hindu. Those who consider India as their ‘matrubhoomi’ (mother land) and want to live with a culture of unity in diversity and make efforts in this direction, irrespective of whatever religion, culture, language and food habit and ideology they follow, are Hindus.” He adds that everyone living inside the boundaries of his imagined 40,000-year-old Akhand Bharat are Hindus.

The over-arching need to find common ground with Abrahamic faiths—by saying that the concept of jihad and a single formless god is in the core of Hinduism or that all people living in India and amidst Indian culture are Hindu—has this understanding at the very heart of it—that Hinduism is somehow inferior to the supremacist, monopolist, violent, and culturally, civilizationally, spiritually, and experientially different faiths. The unreasonable urge to “rise above religion,” or to not appreciate the aspects of Hinduism, is also driven by the same notion of relative inferiority. People possessed with such a notion do not seek to maintain the differences between a Pagan polytheistic faith like Hinduism and Abrahamic monotheistic faiths like Islam and Christianity; or even between the socio-cultural beliefs of Hinduism and the beliefs of Utilitarian globalists.

And why does this particular notion exist in the modern Hindu with such prominence? The answer to this can be traced back to the social reform movements in early modern British India.

The British Raj in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was undergoing a change in attitude towards India. One of the reasons for this change in attitude was the French Revolution, which seemed to inspire revolution around the world, particularly posing a threat to the colonial nations under the British, the long standing enemies of the French. In order to prepare themselves ahead of any French attempts or “inspiration” to destabilise the British Empire, the English from the College of Fort William pressed for a unified Hinduism. Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1765-1837) and Lord Wellesley were central to these efforts [1].

Lord Wellesley was brother of the future Duke of Wellington (who later defeated Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815) and spoke many a time against the French Revolution. As David Kopf notes [2], “a root cause of Wellesley’s actions was, by his own admission, his fear and hatred of France and the very real danger of French expansion into India” [3].

And thus from the College of Fort William commenced reformist interpretations of Hinduism, to turn it into a bulwark against possible “social activism, revolutionary tendencies and challenges to the status quo.”

Colebrooke wrote, under a substantial influence of Jesuit missionaries, that Hinduism was originally—and in its true form—a monotheistic religion with only a formless god at its center. It was thought that the diversity of Hinduism posed a threat to the stability of the British Empire in India in the post French Revolution era.

Hindu reformers such as Ram Mohan Roy followed Colebrooke and aggressively propagated the idea that Hinduism at its core is a monotheistic faith with no room for image worship or idolatry. Roy, walking in the footsteps of Colebrooke’s orientalism, divided the Hindu past into a “monotheistic true era” and the “polytheistic false era”. The latter era, according to him, was destroying “the texture of society” [4].

Later, Ram Mohan Roy founded the Brahmo Samaj with the objective of institutionalising these reformist ideas and interpretations of and about Hinduism. In his attempt, Roy incorporated a large portion of Christian theology into Hinduism [5]. The motives of it, as popularly described by scholars, was to oppose Christian Jesuit activities. But as evidenced from his earlier writings, there was definitely a drive of the orientalist belief behind it which saw Hinduism as originally a monotheistic faith.

The implication of this monist/monotheistic view of Hinduism naturally resulted in attempts to essentially dissolve Hinduism as a separate theology and project it as just another branch of global universal theism. Ram Mohan Roy considered “different religions as national embodiment of universal theism and the Brahmo Samaj as a universalist church” [6].

The social reform movement was carried out against what the reformers deemed to be the backward aspects of Hindu culture, practices, and mores. The goal of the movement was a restructuring of Hindu institutions and beliefs. At the core of these reform movements was dislike or even hatred of polytheism, which is essentially the crux and whole of Hinduism. As a remedy for the ills in Hinduism, Ram Mohan Roy advocated a monotheistic Hinduism in which reason guides the adherent to “the Absolute Originator who is the first principle of all religions” [7]. Roy was essentially incorporating the core beliefs of an Abrahamic faith into a polytheistic religion, labelling it a guiding truth.

What was started by Ram Mohan Roy was taken to even greater lengths and to a much bigger audience by Dayananda Saraswati and his Arya Samaj (founded in 1875). Dayananda studied Vedic literature and aggressively propagated the monotheistic interpretation of Hinduism. Multiple gods, to Dayanand, were a Puranic corruption by the priestly class to control and mislead the masses. And all post-Vedic Hindu literature, including the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, were deemed inauthentic. “Go back to Vedas,” Dayanand proclaimed.

But amidst all this ground-breaking activism lay a highly prejudiced—and possibly Christian-centric—view of the Hindu past. Vedas speak proudly of many gods/deities with hymns dedicated to all of them. It is hard to imagine how this apparent fact could be interpreted into believing that the Vedas propagate monotheism, unless the interpreter has already concluded otherwise. Sure, the Vedas propound grand, cosmic speculation about the origins and nature of the cosmos, with the universe originating “through the evolution of an impersonal force manifested as male and female principles”. So, we find in the Vedas a “tension between visions of the highest reality as an impersonal force, or as a creator god, or as a group of gods with different jobs to do in the universe” [8].

Later the Ramakrishna Mission furthered similar monistic views of Hinduism, terming Hinduism as a religion of all, irrespective of faith or god. The notion of one religion for all, an umbrella theological belief system that could create a universal brotherhood of faiths, was taken to its extreme by the Theosophical Society founded by the Russian spiritualist Madame H.P. Blavatsky and the American Col. H.S. Olcott in 1875. In just nine years the Society had around a hundred branches along with its global centre in Adyar. The Theosophical Society used unconventional and indirect ways to further its ideas of theological universalism and monism. It managed to influence many important personalities who would later go on to change India’s politics via the Indian National Congress. The Society opened many schools and colleges including the Central Hindu College at Banaras.

The British establishment, no doubt, supported, encouraged and institutionalized these reforms, albeit for its own good. With the advent of the eighteenth century, British attitude towards India—which was purely an evangelic utilitarian one—was to somehow do away with the stagnation in Indian society by the work of law and “education” in Christian principles. The zealous goal of these efforts, as Udayon Mishra notes [9], was the creation of a “Europeanised India” with substantial incorporation of Christian ideas and beliefs into Hinduism. Hindu reformer organizations like the Brahmo Samaj, the Arya Samaj, the Theosophical Society, and others played that role exactly, knowingly or unknowingly, playing into the hands of British evangelicals.

This reformist approach of incorporating Christian core beliefs into Hinduism turned out to be a big help to the Christian missionaries and theologians. “By characterising Hinduism as a monistic religion, Christian theologians and apologists were able to criticise the mystical monism of Hinduism, thereby highlighting the moral superiority of Christianity,” Richard King notes. Christian theologians furthered the view that the enormous diversity of Hinduism—in gods, sects, and beliefs—was a sign of inferiority of the Indian stock, thereby making it a responsibility of the British to “educate, civilise, and save” Hindus and India.

“Educating” the Hindus on their so-called monotheistic core was also seen as a step that could help Britishers to club diverse Hindus into a group of single-minded people, easier to govern and less likely to start insurgencies. On the looming prospects of French expansion, an atmosphere of suspicion and anxiety about the stability of British rule led to the furthering of reformed interpretations of Hinduism.

And thus, the anxiety caused by the French Revolution and the British evangelical utilitarian zeal to Christianise India, guided the reformist view of Hinduism. This over-arching need to find common ground with Abrahamic faiths was born out of decades of colonial Hindumesia. – IndiaFacts, 15 December 2022

Footnotes

- Dhar, Niranjan, Vedanta and the Bengal Renaissance, Calcutta, Minerva Associates, 1977.

- As quoted by King, Richard A. H, Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and “The Mystic East”, 1999, pp. 130.

- David Kopf, British Orientalism and the Bengal Renaissance: The Dynamics of Indian Modernisation, 1773–1835, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1969, pp. 46-47.

- Ibid., pp. 199-200.

- Charles H. Heimsath, Indian Nationalism and Hindu Social Reform, Oxford University Press, 1964.

- Dr. Sanjeev Kumar, Socio-religious reform movements in British colonial India, International Journal of History 2020; 2(2): 38-45.

- Heitzman and Worden, eds., “India: A Country Study,” 1995.

- Bijoy Prasad Das, Rammohan Roy: Progressive Role as a Social Reforms and Movements for Social Justice, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention, Volume 10, Issue 6, pp. 57-59.

- Udayon Misra, “Nineteenth Century British Views of India: Crystallisation of Attitudes”, Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 19, no. 4, 1984, pp. 14–21.

› Yogendra Singh Thakur is a freelance columnist from Betul, Madhya Pradesh. He is pursuing his studies, majoring in History, Political Science, and Sociology.